If you are human, you might believe that teeth belong in the mouth. If you are a fish, you already know better. You know that teeth belong in the skin too. These teeth are fittingly called dermal denticles: skin teeth. (Mouth teeth are just called teeth, a testament to how the teeth brand has historically hitched its horse to mouths.) But now a strange fish languidly glides to its place as the latest, greatest innovator in the teeth space, according to a new paper in PNAS. Meet the ratfish, which is also known (more elegantly) as a chimaera or (more mysteriously) as a ghost shark. As a blog of the people, we are calling it a ratfish.

The spotted ratfish, Hydrolagus colliei, is a cartilaginous fish. It grows about two feet long and, despite one of its nicknames, is not a shark. Ratfish and other chimaeras diverged from sharks approximately 400 million years ago, and as such, they look a little strange. Karly Cohen, a marine biologist at the University of Washington Friday Harbor Laboratories and an author on the new paper, first saw a ratfish in the San Juan Islands in 2018. “I grew up on the East Coast and had never seen a fish that looked—or swam—like this,” she wrote in an email. “Honestly, the first thing that caught my attention was the way they moved, almost like they were gliding on wings.”

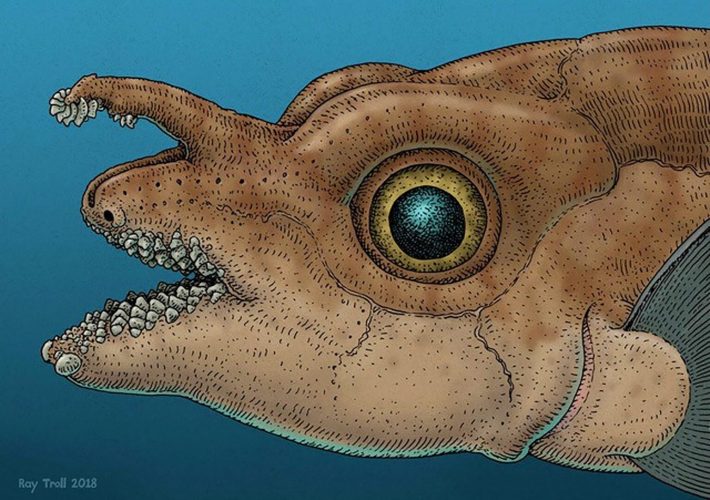

Ratfish have thin and tapering tails and their brownish bodies are pleasantly dappled in fawn-like spots. Even more anatomical eccentricities lurk inside the fish. While sharks have conveyor belts of individual mouth teeth, ratfish have teeth plates used for grinding. But somewhere between the ratfish’s eyes sits a small white bump. This is the tenaculum, a retractable rod tipped with a chandelier of teeth. As with other appendages, the male ratfish uses his forehead tenaculum for sex, specifically to grab onto a female partner during the act (a pair of pelvic claspers also assist in this goal). “When retracted, it looks like a little peanut or pimple wedged between their eyes, but when it flips up, it’s like a hooked rod covered in cat-claw shaped teeth,” Cohen said. “The first time I saw it extend, my instinctive reaction was that the fish was flipping me off.”

Cohen and her colleagues became interested in this unusual appendage and the teeth that sprout, porcupine-like, from its tip. What kind of teeth did they represent? Mouth teeth? Skin teeth? A third, unknown type of teeth? While all modern sharks are covered in sandpaper-like dermal denticles, ratfish are utterly smooth (hence yet another nickname, “naked sharks”). As such, “it would have been surprising if these forehead teeth turned out to be just another version of skin denticles,” Cohen said.

To determine the nature of the forehead teeth, the researchers collected spotted ratfish of all ages from the San Juan Channel in the Pacific Northwest. They scanned the specimens to study how the tenaculum grew with the ratfish. On embryos, the appendage resembles a pimple. It later attaches to jaw muscles and eventually emerges from the fish’s face, barbed with teeth. They found that both young male and female ratfish grew tenaculums, but only the males’ rods made it to adulthood.

When the researchers analyzed the tenaculum’s tissue, they found the teeth had what’s known as dental lamina, the structure that seeds new teeth in a jaw. In other words, the forehead teeth were mouth teeth after all—”true teeth,” according to science. Molecular tests supported this evidence, finding tooth-related genes in the tenaculum. So ratfish somehow managed to grow mouth teeth not just outside the mouth, but outside the head. “Very weird,” Cohen said. “Most fish keep their teeth inside their mouths, of course.” The researchers believe the spotted ratfish is the first vertebrate to grow mouth teeth outside the jaws, she added. And the presence of the lamina suggests that the tenaculum does not just grow mouth teeth; it has the potential to replace them.

The researchers also looked to the fossil record of a prehistoric chimaera, Helodus simplex, which has a primitive sort of tenaculum that sprouted closer to the jaw with a tight whorl of teeth. So the spotted ratfish’s forehead teeth are not something entirely new, but represent a lineage of mouth teeth popping up outside the mouth. “It’s part of a much longer evolutionary story,” Cohen said.

To Cohen, the most significant aspect of the research is that the dental systems of fish and other vertebrates are more flexible than scientists thought. “It’s a striking example of the kind of developmental tinkering we’ve theorized about but rarely get to document with this level of detail,” she said.

By challenging the long-held orthodoxy that teeth are locked into the mouth, the spotted ratfish has opened up space for even more innovations in teeth. Cohen now finds herself on a quest of sorts. “Where else might we find true teeth?” she wondered. “If we broaden our definition of what counts as a tooth and where they can form, I think we’ll start noticing them in more unexpected places across vertebrates.” So stay tuned for the exciting future of teeth, which refuse to be contained by the stodge of tradition, and will grow wherever they see fit.