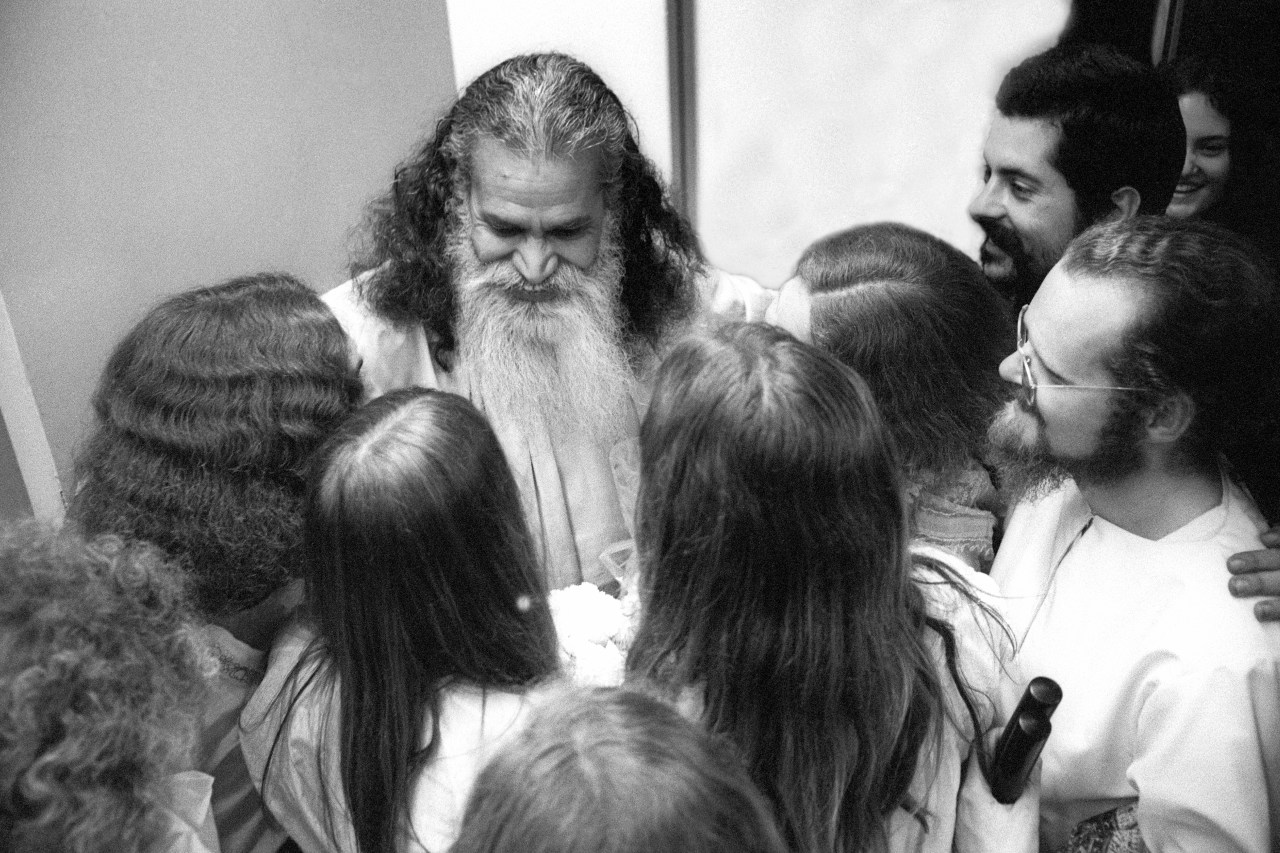

The guru sat cross-legged on the stage, looking out on a sea of hundreds of thousands of hippies.

It was Aug. 15, 1969, and the sweaty masses had gathered on a dairy farm in Bethel, N.Y. to see Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead and more perform as part of the legendary Woodstock music festival. But before those iconic performances could begin, Swami Satchidananda, an Indian spiritual leader, had been tapped to deliver the opening invocation. He sat with his back straight, his orange robe hanging off his thin frame, and spoke into the microphones.

“America is helping everybody in the material field,” he said. “But the time has come for America to help the whole world with spirituality also.”

Satchidananda, later dubbed the “Woodstock Guru,” would take a prominent role in that effort and, in doing so, became something of a spirituality rock star for a time, counting Baby Boomer celebrities like Carole King and Dr. Dean Ornish among his followers. He built and presided over a small spiritual fiefdom for the rest of the century, launching Integral Yoga Institutes across the country, including in New York and San Francisco.

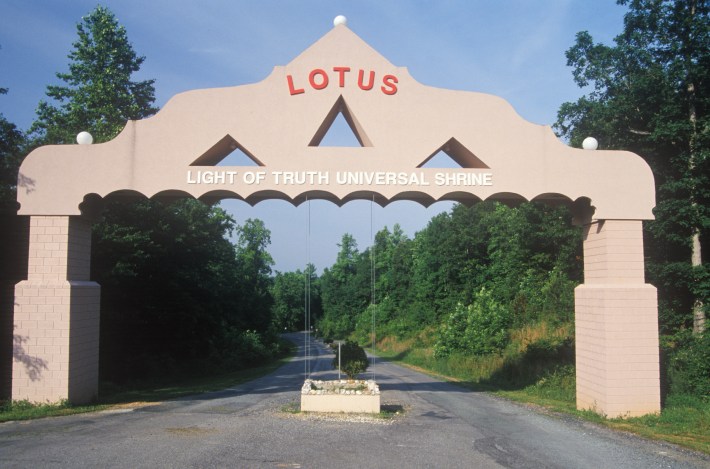

The crown jewel of his empire was the Yogaville ashram in Buckingham, Virginia, a 750-acre enclave where hundreds of devotees lived and followed Satchidananda’s way of life, practicing yoga and meditation, eating a vegetarian diet, and abstaining from drinking and smoking. On ashram grounds was the Light of Truth Universal Shrine (LOTUS), a massive, dome-shaped interfaith temple. Followers engaged in devotional practices in an effort to cultivate “seeing the guru as god,” one longtime follower said.

Though Satchidananda died in 2002, at the age of 87, Yogaville remains an active yoga community. Satchidananda’s influence is strong, with his word spoken as gospel and his photos decorating the property, which is known as Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville. The guru was interred at the ashram, and above where his body rests in a marble case is a wax figure meant to resemble him, said Brianna Patten, a former resident of the ashram. A tube connects the marble case to the wax figure, Patten said.

“They say this is so his energy can go from the body into the wax figure,” she said.

Patten, a Delaware native, arrived at Yogaville in 2015 after a difficult first two years at Towson University. Life at Yogaville, with its spiritual community and emphasis on healthy living, brought Patten a sense of inner calm. She started renting Satchidananda’s old trailer on the property, she said, overlooking the James River.

But by 2018, Patten grew disillusioned with the ashram. It had started to feel “cult-like,” she said. Then, in 2019, Patten found a New Yorker article titled “Yoga Reconsiders The Role Of The Guru In The Age of #MeToo,” detailing allegations of sexual misconduct against several gurus from decades past, including luminaries like Bikram Choudhury and K. Pattabhi Jois.

And Swami Satchidananda.

In late 2021, Netflix released Tiger King: The Doc Antle Story, a three-part true crime exploration of a big cat zoo owner accused of abuse and intimidation and, in his earlier days, maintaining a harem with mostly underage women (and a modern day harem with adult women as well). The documentary painted Antle as a megalomaniac and master manipulator obsessed with power. His persona, according to those interviewed, was shaped in large part by his former guru, on whose ashram he lived and met younger women: Satchidananda.

“Swami Satchidananda used to always laughingly say that yoga institutes were asylums, and we were all the inmates,” Joan Cichon, a former Yogaville devotee, said in the documentary. “People would go ‘Ha ha ha! That’s so funny Swamiji. But it was true.”

On Jan. 22, 2022, members of the community gathered for a “healing circle” Zoom meeting to discuss the series, hosted by the Yogaville Community Association, which has since changed its name to the Village Sangha Association. That same year, David “Vijay” Hassin, a longtime member of the sangha, emailed a letter to leadership asking the organization to formally acknowledge accusations of sexual misconduct committed by Satchidananda. In July 2022, Shanti Norris, one of the guru’s former personal assistants, wrote a letter to Integral Yoga leadership revealing she had been in a 10-year sexual relationship with Satchidananda.

“He took advantage of many of his female students’ innocence and adoration and continually mimicked the life of a celibate monk while living differently,” Norris wrote.

The guru, who preached that “truth is one, paths are many,” had previously been accused of abuse by female followers in the 1990s. But the #MeToo movement, Tiger King, and Hassin and Norris’s letters pushed the long-forgotten allegations against Satchidananda back into the community’s consciousness. To some, it felt past time for the organization they loved to embrace a more complete version of the guru.

In October 2022, Yogaville and Integral Yoga leadership finally addressed the comments—but stopped short of taking accountability.

“It is not possible for the organization to make a statement on his behalf or to definitively comment about consensual relationships, or allegations of comments of a sexual nature or sexual advances that are alleged to have occurred thirty to fifty years ago,” the statement read.

A year later came the lawsuit. In November 2023, Norris and Susan Cohen sued the Integral Yoga Institute (IYI) and Satchidananda Ashram–Yogaville for five causes of action, including sexual discrimination and gender-motivated violence. In March 2024, Yogaville and Integral Yoga countersued Cohen and Norris for tortious interference with business relations, libel, and slander. Norris and Cohen then filed a motion to dismiss Yogaville’s counterclaims, based on New York’s anti-SLAAP Law.

On Dec. 17, New York County Supreme Court judge Lyle E. Frank dismissed all of Yogaville’s counterclaims. Yogaville and Integral Yoga’s attorneys filed a notice of appeal.

Early in the process of reporting this story, a lawyer for Yogaville and Integral Yoga, Wayne Wilansky, responded to a request for comment. He said: “The organizations acknowledged the allegations to the extent that they could, being that the person they’re making allegations against has been dead for 22 years.” Messages left for comment with Yogaville and Integral Yoga did not receive any response. Defector reached out to Wilansky several more times closer to publication with a detailed list of questions based on its reporting. Wilansky did not reply until early June.

“It’s pretty clear from your last email,” he said in a voicemail, referencing a list of questions sent in March. “The reason I didn’t respond to it, it’s pretty clear that you are intending to write a one-sided article slanted in a direction that’s not accurate. So I have no intention to respond to that.”

But when Defector called back Wilansky, the attorney laid out the organizations’ perspective over a 25-minute phone call. He said he remained confident the lawsuit will be dismissed.

“The allegations in the complaint are preposterous, they are completely against the actual facts,” Wilansky said. “The women are basically saying, as adults, because they are adults, that they were incapable of giving consent, is what they’re saying. And that’s utterly ridiculous. … There’s absolutely no question that there’s no person here on Earth who had non-consensual sex with Swami Satchidananda.”

Carol Merchasin, the attorney for Cohen and Norris, declined to comment on the specifics of the lawsuit and the counterclaim but said in a written statement that “both courts and society have recognized that psychological coercion can strip even adults of the ability to say no. It’s long past time to bury the outdated myth that silence equals consent.”

The chaos surrounding the organization has led to financial harm, according to court documents. Radha Metro-Midkiff, executive director of the Integral Yoga Institute New York, wrote in a July 2024 affirmation that the organization’s overall income was “down 17 percent compared to the same period as last year.”

“It has been hard for us to secure presenters and trainers to help us replace all of this lost income,” Metro-Midkiff wrote.

In a July 2024 affirmation, Prem Anjali, Satchidananda’s personal assistant in the final years of his life, blamed Norris’s public statements for the organization’s financial troubles. “The organization experienced staff resignations, program cancellations, and distancing from affiliated organizations, loss of students and potential donors, severely impacting its financial stability,” Anjali wrote. “The actions of plaintiff Norris … have caused significant financial harm that was intentional and motivated by malice.”

Yogaville is far from the first yoga community to have its leader accused of abuse. Here are just a few of those leaders: Choudhury, the founder of Bikram yoga; Jois, the founder of Ashtanga yoga; and Greg Gumucio, founder of Yoga to the People. It’s happened enough that there’s an entire Wikipedia page dedicated to them.

Defector reviewed the court records, spoke with two other women who said that Satchidananda unexpectedly engaged them in confusing sexual experiences, and also spoke with five people who were or continue to be a part of the Yogaville community. Taken together, they cast a light on one yoga community—but almost surely not the only yoga community— that, all these years following #MeToo, still struggles with a basic question: What do you do when your guru is named as an abuser?

Susan Cohen’s journey to Satchidananda began with a song.

It was 1969, and Cohen, then 17, was at the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island when she met two institute students, the lawsuit said, singing songs and talking about Satchidananda’s teachings.

The Vietnam War was raging and Cohen, as she later wrote, felt a responsibility to help bring a brighter version of humanity into the world. Instead of attending college, she moved to Manhattan and, according to the lawsuit, got involved with the institute.

It was not long before Cohen was working six days a week at the institute as a cook, receptionist, and yoga instructor. The institute discouraged her from contacting family and friends, but she also landed private yoga instruction from Satchidananda, in which, according to the lawsuit, he told her to tell herself: “Don’t think. Don’t question.”

Cohen also wrote about what happened on gurusexabuse.com, a website created in July 2023 to document reports of Satchidananda’s alleged abuse. “The IYI philosophy was strict and said that to be a serious disciple, one must practice poverty, chastity and 100 percent obedience,” Cohen wrote. “I did not know then how detrimental this can be when one allows another person’s will to overtake their own and how after a short time, it is no longer voluntary.”

By about 1971, Cohen was tasked with serving Satchidananda meals and giving him foot massages, the suit said. Satchidananda also started asking Cohen about her sexual experiences. On one occasion, according to the lawsuit, he touched Cohen’s face and breasts without her consent. On another, the lawsuit said, he instructed her to perform oral sex.

“Use your mouth,” she recalled him telling her.

Cohen kept quiet about these experiences because she feared losing her job, but by the following year, she was considering leaving. According to the lawsuit, Sylvia Shapiro, a student, had just publicly accused Satchidananda of sexual abuse—and was subsequently pushed “out of the community.” But then the Institute offered Cohen a new job as the guru’s secretary.

“Why didn’t I say no? I had plans to go to college and live with friends,” Cohen wrote on gurusexabuse.com. “It didn’t make sense except that I was used to not asking myself what was best for me and had no idea of how critical thinking could transform my life for the better.”

Over the next few years, according to the lawsuit, Satchidananda sexually assaulted Cohen during trips to Europe, Israel, Dallas, Chicago, and Santa Barbara.

“She did not tell anyone about it because she feared losing her job and being driven out from the community at the Institute,” the suit says, referencing Shapiro’s shunning after she came forward. “Cohen saw what had happened to Shapiro and did not want to suffer the same fate.”

Cohen left the organization around 1980. About a decade later, though, she began to speak up about what she said had happened to her.

“It is psychologically very damaging to women to have this happen with a father figure,” Cohen told the Richmond Times-Dispatch in 1991. “The fact he will not address this publicly is a big part of the problem. The secrecy reeks of dishonesty. It’s a terrible contradiction in yoga. Yoga is supposed to be open and dedicated to the truth.”

Satchidananda forcefully denied Cohen’s allegations. “If they don’t feel comfortable with me, they can go learn from someone else,” he told the Times-Dispatch. “I believe that God is using me as an instrument. I am just there, like a river is there. Those who want to come and take a bath may do so. Those who do not want to do not have to.”

Protests were held in support of Cohen and Shapiro, who, 20 years later, had renewed her public fight against Satchidananda. (Shapiro died in March 2023.) Protestors held signs that read “Help stop the abuse, end the cover up!” and “Blind faith is a hazard to your health. Question authority.” But the protests came and went and, as former students described it, Yogaville continued on like normal.

In the counterclaim, Yogaville and Integral Yoga concede that Satchidananda had a consensual sexual relationship with Cohen— while painting Cohen as a jealous woman set out to destroy the guru’s character:

“It was this rage, caused by not having SS all to herself, that resulted in her deep resentment of SS and the Organization (s). She either wanted a marriage to SS or a continued exclusive sexual relationship. His declination of that desire caused and causes her to maliciously attack the Organization (s).”

The same year Cohen discovered Satchidananda through music, Shanti Norris auditioned for him. Satchidananda had been booked to make a speech at Carnegie Hall in January 1969, and in advance of the event, he auditioned several students to perform poses beside him on stage, the lawsuit said. Among them was Norris.

“As she performed the various movements, Norris felt Swami Satchidananda stare extensively at her body and look it up and down,” the lawsuit says. “Soon after this uncomfortable interaction, Swami Satchidananda selected Norris to join him onstage for the speech.”

Norris had been attending college in New York City in the late 1960s when she became involved with the institute, where she studied to become a yoga teacher. Not long after the audition, Norris and several students met Satchidananda for dinner at an Indian restaurant in Harlem, the suit says.

On the drive home, Satchidananda asked Norris to join him in the front passenger seat, her lawsuit said. In the Volkswagen Beetle, Satchidananda told Norris to sit on his lap and he “proceeded to fondle her breasts, without her consent, out of view of the other passengers,” the lawsuit said. Norris froze.

That same year, she dropped out of college and accepted an offer to become Satchidananda’s assistant. Part of her responsibilities, per her lawsuit, involved giving Satchidananda massages.

On July 20, 1969, less than a month before Satchidananda’s star turn at Woodstock, he and Norris watched Neil Armstrong become the first person to step foot on the moon. They were staying together in Los Angeles, and later that night, Satchidananda told Norris a student must be naked in front of their teacher, according to the lawsuit. Norris believed this to be a metaphor.

“Swami Satchidananda then instructed Norris to remove her clothes and stand completely naked in front of him. In a state of confusion, but fulfilling her expectations as a student and employee, she complied,” the lawsuit said. “Norris disrobed in a nearby bathroom and presented herself naked to Swami Satchidananda, who then embraced her, commended her for her obedience, and covered her body with a blanket.”

The following day, as Norris was massaging his legs, Satchidananda “pulled on Norris’s arms and signaled to her to lay down,” her lawsuit said. He then sexually assaulted her. Norris froze during the attack, per the lawsuit. She kept working with him for years afterward, even after more sexual assaults, the lawsuit said, for fear that if she spoke out she would lose her job.

“Norris did not want to have sex with Swami Satchidananda but worried she would be removed from her position as an assistant if she resisted him, said no to him, or told anyone else about the abuse,” the lawsuit says. “Norris found the courage to tell Swami Satchidananda that she felt that he was using her for sex. He disregarded her feelings and went on to mock and mimic her repeatedly for expressing herself.”

Finally, in 1979, Norris left the institute. In a November 2022 letter addressed to Yogaville “ministers and friends,” later posted online, Norris said she had tried to convince leadership to hire “an outside consultant to help move the organization through an honest, comprehensive and facilitated healing process.”

In response to her lawsuit, Integral Yoga and Yogaville’s counterclaim painted a different picture of Norris, calling what happened with Satchidananda and Norris at-will and consensual due to a “deep love and endured over a ten (10) year period.”

The counterclaim also said Norris was, in fact, the “person most singularly responsible for the organizations’ response to plaintiff Cohen” in the early 1990s. Per their counterclaim, Norris turned on Yogaville in response to the passage of the Adult Survivors Act in New York. As part of their response, Yogaville included a copy of a 1992 letter published in Yoga Journal in which Norris wrote that she had “never seen him act or speak in a sexual way to women.”

In reference to women who had accused the guru of misconduct, Norris wrote: “I believe the background and motivation of people making allegations should be looked into. A true guru-discipline relationship is very strong and dynamic. A student accepts that the spiritual master knows more and allows him or her to work on the ego—the very thing we most defend and protect.

“As many of you and your readers know, it is often a painful experience,” Norris continued. “There are even prayers we say in order not to develop resentment toward the master in the process.”

In their legal response, lawyers for Norris wrote: “These words constitute harassment and intimidation and are intended to punish Norris for coming forward about her decade of sexual assault. And they are in no way relevant to the Counterclaims—which fail as a matter of law.”

Rick Alan Ross, founder of the Cult Education Institute, has been studying cults for more than four decades. He said he has testified as an expert in court cases involving what he described as “authoritarian” groups—some of which have been described as cults—in 13 states. (On a recent phone call, he excused himself to hand off expert witness documents to a FedEx representative at his door. He said the documents would be submitted as part of a court proceeding involving Lev Tahor, an extremist religious sect from whose compound Guatemalan officials recently rescued about 160 children.)

Ross said there’s a difference between so-called “benign” cults, like fans of Taylor Swift or Justin Bieber, and “destructive” cults, like Lev Tahor, members of which he said are “hurt systematically as mandated by the leadership.” He points to three core characteristics, developed by psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton, that he uses to identify a destructive cult: a charismatic, authoritarian leader who becomes an object of worship; coercive persuasion, or thought reform; and exploitation of the members by the leadership.

Ross has been following Yogaville for decades, talking to ex-followers and family members of followers, and posting those accounts, as well as legal and financial documents and newspaper articles, to his website. The bulk of his research into the group came before Satchidananda’s death.

“When Satchidananda was alive, it certainly, in my opinion, was a destructive cult,” Ross said of Yogaville and Integral Yoga. “In my opinion, he left behind a legacy of a cultic organization.”

When asked for comment, Yogaville’s lawyer, Wilansky, said Ross was “full of b.s.” and pointed to the success of so many Yogaville devotees as proof of Satchidananda’s positive influence.

“What’s very interesting to me is, a lot of the people, and even the plaintiffs themselves, people who surrounded Swami Satchidananda as young kids, hippies with no particularly bright futures ahead of them, all wound up getting doctorates or doing really great things with their lives, you know?” he said. “So something was going on right as well as whatever else is being talked about.”

Yogaville’s legal response characterized Ross’s research as Ross collaborating with Cohen to “damage” Yogaville. “That is a ridiculous claim without any basis in fact whatsoever,” Ross replied, adding he might have spoken to Cohen more than two decades ago but couldn’t recall. “We certainly didn’t have an ongoing series of anything,” he said. “I may have spoken to her once.”

Ross is less familiar with Yogaville and Integral Yoga’s modern operation, and for that reason, he stopped short of declaring the present iteration of the organizations a cult.

Cohen and Norris are the two women named in the complaint, but the list of female students whom Satchidananda allegedly abused stretches to at least 10, according to the lawsuit. Two women who did not file lawsuits also spoke to Defector about what they described as unexpected sexual encounters with Satchidananda.

Leela Marcum said she first encountered Satchidananda and his teachings just after college in 1969 while living in Dallas, where she felt out of step with a culture that encouraged women like her to “cut my hair in a certain way and be a debutante.” Marcum had long been searching for a community of like-minded individuals interested in eating a vegetarian diet and practicing yoga and meditation. “The moment I walked into that environment, I felt so at home,” she said of the Integral Yoga community.

In the 1970s, she moved to the Integral Yoga Institute of San Francisco and soon became the accountant for all of the institutes and centers in California. When Shapiro went public with her allegations of sexual assault two years later, Marcum felt conflicted.

“I had no doubt in my mind that she was abused,” Marcum wrote on gurusexabuse.com, later adding, “I felt I needed to find a way to forgive Swamiji.”

She’d burrowed deeper into the teachings, and in 1973 took pre-sannyas vows, meaning she was training to become a monk. The following year she decided to move to the new Yogaville ashram in Connecticut, after a pit stop at her parents’ home in New Mexico. Satchidananda stayed with Marcum and her family for a few days—he visited because he wanted to visit the Los Alamos National Laboratory, where Marcum’s dad had worked—and then the two, along with two more followers, boarded a train, she said.

At the train station, Marcum recalled her father asking Satchidananda to take care of her. “Swamiji’s reply to my dad was, ‘Don’t worry, the minute she tells me she’s attracted to somebody, I’ll have her married like that,’ snapping his finger,” Marcum said.

Satchidananda, to whom Marcum, then 26, had donated all of her savings as part of her vows, arranged for them to share a cabin on the train; Marcum in the top bunk, Satchidananda on the bottom. On the first night, as they were getting ready to sleep, Satchidananda asked Marcum to come down to give him a foot rub. Not long into the massage, she said, Satchidananda put his hand down her pants and placed her hand on his genitals. Marcum, whose vows also included a commitment to celibacy, pushed the guru off of her and sat up from her seated position on the bed.

When she sat back down, Satchidananda’s head ended up in her lap, and she rocked him like a baby.

“Now I’m looking down at my guru. I said ‘I still love you,'” said Marcum, who hypothesized that Satchidananda had been testing her. “I didn’t sleep a wink the whole night. I was nervous.”

The next morning, Marcum said, Satchidananda told her he didn’t want to see her anymore. She spent the rest of the trip crying. She said she didn’t report the incident to police because she didn’t have a witness and felt it would be better for her well-being to not make a big deal out of it.

Marcum’s exit from the ashram came after she gave up her plans to be a monk and got married. She had found herself “terribly attracted” to another member of the sangha, and tried to avoid him. She was unsuccessful, and Satchidananda married the couple at the ashram, about eight or nine months after the train incident.

“I have a photo of Satchidananda standing between the two of us, and we’re all three holding the knife to cut the cake,” Marcum said, chuckling. “I’ve got to laugh at it. It’s ridiculous.”

Not long after the marriage, she told her husband, Robert “Ramesh” Marcum, about what happened.

“I was proud of her for not really succumbing. She paid a big price for it, though,” Robert Marcum said, referencing Satchidananda’s treatment of his wife after the alleged incident. “But she would’ve paid a bigger price, in our minds, going forward, if she had succumbed. And I think the other people involved would tell you the same thing.”

Decades later, after Satchidananda’s death, Marcum first started telling people about what happened. But when she approached one of Satchidananda’s oldest devotees at the ashram, she was told that she simply didn’t understand Indian culture.

“She just said that the relationship between the guru and the disciple is very private,” Marcum said. “She was normalizing it.”

Defector reached out to the devotee mentioned by Marcum, but they did not reply to any requests for comment. Wilansky did not respond to a detailed list of questions about Marcum’s claims, but said over the phone, “That’s not the way I heard the story.”

“The way I heard the story was that she was asked if she would have sex with him and she said no and left the train compartment and that was the end,” Wilansky said. “The versions of the story that I heard indicated that nothing happened, that he asked her and she said no. Many men ask women if they’d like to have sex, if they say no and they don’t have sex, there’s nothing wrong with that.”

Sharada Thompson was just 17 when she just moved into one of the Manhattan institutes around that same time. Since she was younger than 18, her father needed to sign a release so she could live there, she told Defector.

She had anxiety growing up, she said, and her father was emotionally abusive. After a panic attack led her to drop out of school, she turned her attention toward spirituality, dabbling a bit with LSD. And then she met Satchidananda.

“He treated me like a child,” Thompson said. “I remember him holding me in his lap and telling me I never have to be scared again.”

Early in Thompson’s involvement with the organization, Sylvia Shapiro spoke up about her alleged abuse by Satchidananda. Thompson, who by then was one of Satchidananda’s part-time secretaries, had grown up in the same part of Long Island as Shapiro.

“He would cry in my arms every day. He’d say ‘How can these children say these things about me?'” Thompson said. “‘If you talk to your friend [Sylvia], you won’t love me anymore.’ I assured him I would never believe any of this and that I loved him. That was the state I was in, until he seduced me in a hotel room a couple years later.”

One evening, in a hotel in the Midwest, Satchidananda called Thompson into his room to give him a massage. Satchidananda then rolled Thompson over and, she said, they had sex.

Thompson told Defector she now considers the encounter to have been sexual abuse, though she didn’t at the time. When she returned to her room, it felt like her “world crashed.” She was 19.

“I could not take in what had happened,” she said. “It was not very long and then it was done. I had no sense at all of having been physically harmed. I had a sense of being completely betrayed.”

She started furiously writing down her thoughts on what had happened, and what it all meant. She slipped the notes into her carry-on suitcase. On the flight home, amid an intense storm, Satchidananda pretended over and over again to peek into Thompson’s luggage, as if he knew there was something in there she didn’t want him to see.

“He seemed to think it was kind of amusing,” Thompson said. “I was in a dark night of the soul that was really quite overwhelming.”

Thompson soon left the ashram and, eventually, returned to school. She carved out a fulfilling life: She got married, and earned a doctorate degree in clinical psychology. She pushed down the pain of what had happened with Satchidananda, and tried to minimize its importance.

Then, a few years ago, she reconnected with longtime member David Hassin on an online dating platform. Soon they were inseparable, and eventually they married. As they reminisced about the past, conversation turned toward Satchidananda’s alleged abuses, and Hassin’s efforts to get Yogaville and Integral Yoga to acknowledge the allegations.

Thompson kept what happened to herself for decades. Then, in November 2022, for the first time, Thompson went public with her story, and called on the sangha to embrace a more complete version of their guru.

“The truth is that Swamiji had sex with a number of women … Let Swamiji be a real and complicated human being,” she wrote on gurusexabuse.com. “Please don’t compromise your goodness and integrity out of fear or a childish need to make the world a simple place of black and white intentions. Gurus are not gods.”

When asked for comment, Wilansky did not respond to a detailed list of questions about Thompson’s experience. But in a phone interview, he said, “I don’t want to make any comment on Sharada. Whatever Sharada has to say, she can say it in a deposition if she’s going to come forward and participate.”

Those who speak out publicly against the guru are often shamed, said Kathleen Rosenberg, a former member who created a Facebook group for followers to discuss what was being said about Satchidananda. Rosenberg, who took her first Integral Yoga class in 1972 at the age of 15, believes Satchidananda’s accusers should be acknowledged and supported. But she also does not want to completely write off Satchidananda, his teachings, and their community.

“In the sangha, there’s so much love there,” she said. “We’re angry. We’re divided, but we love each other, bottom line. We share the same lifestyle and the same values that we learned from Satchidananda.”

Where Rosenberg diverges from some is her desire for healing. In its early days, her Facebook group became something of a battlefield: Longtime members argued back and forth about Satchidananda, the accusers, and what their words should mean.

Rosenberg said so-called “deniers” were printing out comments calling for the ashram to acknowledge the women, and then giving them to Yogaville leadership. One person whose comments had been printed out told Rosenberg he was subsequently shunned from the ashram.

Rosenberg recalled a conversation she had with a monk over Facebook messenger.

“I wish you the best, but there is no point in to trying to change the stand of the central power,” the monk wrote. “It is all about strong religious faith and you really can’t argue with that, faith is strong it stands above all else.”

Satchidananda had preached in the early days that disciples should not worship him, Rosenberg said, but in recent years, she observed, some had started to cast him as a religious figure.

In a December 2022 post in Rosenberg’s Facebook group, a person posting under the name Swami Premananda: “We look upon the Guru as God so we can fully receive what is coming through him.”

“That’s the fundamental mistake right there,” Rosenberg said. “I never saw Satchidananda as god.”

Hassin, the former president of the California institute when Shapiro came forward, echoed that sentiment. In the 2010s he started attending events at Yogaville after several decades away from the organization, but found himself uncomfortable with the level of veneration for Satchidananda.

“They started to say he was the level of Krishna, Buddha, Jesus,” Hassin said. “That was a point in which I was going, ‘I’m sorry, I can’t go there.'”

Marcum said she sometimes receives messages from Satchidananda defenders accusing her of fabricating her story.

Patten, the former ashram resident, left the organization after the administration’s response to the allegations, but not quietly. She has regularly notified people scheduled to make presentations at Yogaville of the allegations against the guru, leading to the presenters cancelling their appearances, she said. Wilansky said the organizations notify people interested in participating in yoga training or working as a yoga teacher of the allegations and the lawsuit.

The webmaster for gurusexabuse.com would not identify themselves but told me—through a message a former follower shared with me—that they started the website to give a voice to the women’s stories, and no Satchidananda defenders had reached out to them about the site’s contents.

“I’m not even sure they look at the website,” the webmaster wrote. “They seem content to ignore the actual testimony of the women, maybe because the truth is too threatening to their beliefs about the guru’s perfection.”

Wilansky conceded some might consider Satchidananda “god-like,” while others merely saw him as a man full of wisdom. But he laughed off suggestions that a power imbalance between a guru and a follower could lead to an unhealthy sexual relationship.

“Is there a human being on the planet that he could’ve had sex with where there wouldn’t have been a power imbalance?” Wilansky said, chuckling. “The Queen of England, or something … To me it seems absurd to expect that any human being who is sexually active, a normal human being, would not have sexual activity in their lives at all. That seems where we get into problems, with expecting that people won’t have sex.”

Asked about accusations of hypocrisy, given the fact that Satchidananda claimed celibacy, Wilansky said, “I don’t care.”

“He’s a man. Do you know any men who don’t want to have sex with women?” Wilansky said. He maintained Satchidananda was a force for good in the world and affected “tens of thousands of lives in a positive way.

“A lot of people who needed help in figuring out their lives, learned to meditate and to do yoga and to use those things as ways to not do drugs, and other stupid things,” he said. “Given the choice between shooting heroin and meditating, I think meditating might be the way to go.”

A couple years ago, as I started researching this story, I came across a chatbot called “Ask Swami,” meant to pull on Satchidananda’s teachings to impart wisdom. I asked the chatbot if it was true that Satchidananda had abused his accusers. The technology was ready with a response:

“To suggest that Swami Satchidananda violated his own teachings by harming his followers,” the response read, “is similar to believing that the peaceful lake might rise and overturn the boats sailing on it.”

I have practiced yoga on and off for about 10 years, as a way both to stay fit and to ease a chronically anxious mind. If I had come of age in Satchidananda’s time, I could see myself falling into his orbit and all that it offered: Community. Health. Peace. Love.

After the articles, the lawsuit, the Facebook group, everyone who spoke up, it still looked like business as usual at Integral Yoga to a drop-in yoga student last spring. On a steamy Tuesday evening in late May 2024, I went to the Integral Yoga Institute on West 13th Street in Manhattan. After months of studying Satchidananda, reading the legal documents, and talking to people who said they were harmed by him, I wanted to experience one of the last remaining vestiges of his empire.

I was greeted by a smiling woman seated behind a desk on the first floor, who seemed delighted when I told her this was my first time at the Institute; she did not know I was a reporter. She smiled and directed me to take the old, creaky elevator to the sixth floor—the highest in the building—where the 6:45 p.m. class was being held.

The 80-minute class, also attended by five older white men, was taught in the yin style of yoga, which emphasizes slow, deep stretching. By the end I felt loose and rejuvenated, and afterward I thanked the instructor, a white woman with curly brown hair. Satchidananda was not mentioned during the class, but I noticed a shrine at the front of the room, featuring one photo of Satchidananda and one of his guru, Sri Swami Sivananda.

After class, the instructor told me that the room we were in actually had been Satchidananda’s apartment when he stayed in New York. I looked around and tried to imagine the guru moving around the space, looking out the window onto the New York skyline, sitting in lotus pose, contorting his body into all sorts of complicated yoga moves. I silently hoped nothing nefarious had happened there.

Before I walked down the staircase, the walls of which were decorated with photos of Satchidananda, I peeked at a legend denoting the names of each floor in the building.

The top floor, where Swami Satchidananda had once lived, is called Heaven.