DUBLIN — It’s raining. In Dublin this is as predictable as the phases of the moon. So predictable that I prewrote this lede. But I was right: It’s raining.

I’m in the capital chasing a fascination of mine. I turn off a modern thoroughfare and squeeze my Yaris down a narrow residential street. Older brickwork houses and apartments stretch around a maze of similar streets ahead of me. Just before the houses, I find my quarry. The Hercules Club, founded 1935, is Ireland’s oldest gym and fully owned and operated by its members.

The gym is now housed in a converted centuries-old home, bought by the club in 1985 and only recently paid off. Finding the entrance is a bit of a quest, but I eventually discover two means of access: a card scanner for members, and a doorbell for guests. I hit the bell and instantly hear footfalls approach. Stephen Hynes, a member of the elected committee of members that runs the club, opens the door and looks at me with a searching expression. I get the sense they don’t get a lot of visitors.

“Jasper,” I stretch out my hand.

His face changes to a smile, and in we go.

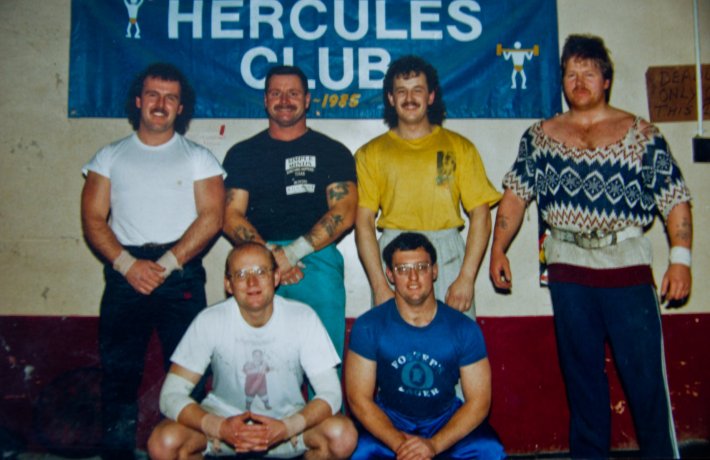

We tour the gym’s three floors while he peppers me with history, both community and personal, often intertwining. The ground floor is the heavy stuff: the powerlifting and Olympic lifting platform, the heavy dumbbells, the squat racks, and so on. An ancient lat pull-down machine sits next to modern calibrated plates. There’s a massive banner at the far end with the club’s logo, looking to me like something from a school dance (I assume).

This floor is Stephen’s domain. He started as an Olympic-style lifter, but he claims he never had that drive that makes someone a competitor. He settled into heavy strength and conditioning over the years, but he still holds a special affection for the sport he was trained on. He talks about how, for such a sporting country, few have represented the Republic at the weights. It’s a long road to the Olympics for any athlete, of course, but the road is a lot rockier for an Irish weightlifter. “The Irish IOC never much liked weightlifting,” he explains. “The steroids and all that.”

The gym is quiet. A handful of members are warming up in that monk-like way of serious competitors (one I speak to is a high-level competitive powerlifter). Music is bumping at very modest volume; most gymgoers have Airpods in, anyway. Pictures, mostly black-and-white, line the walls. Some commemorate members’ accomplishments, like Bernie Delaney’s 262.5 kg bench at the World Powerlifting Championship, Las Vegas 2009. He claimed his fourth world championship that year. I spot a couple of competitive bodybuilding photos as well—spray-tanned and striated bodies who trained here on their way to a pro card.

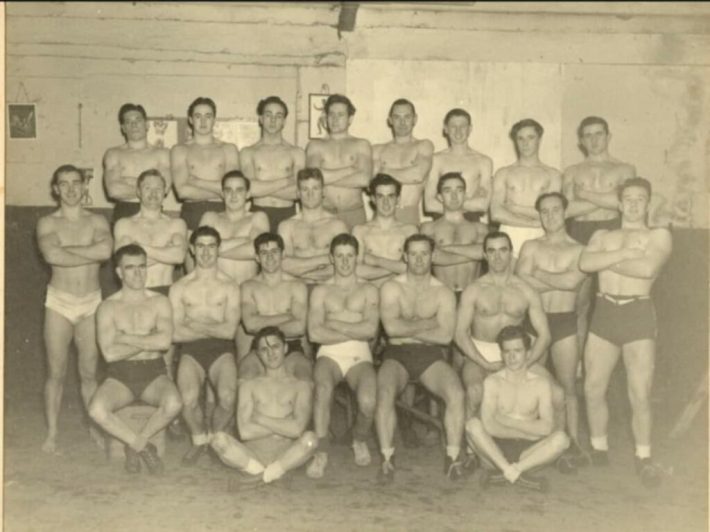

Many of the photos are group shots of the club’s General Meetings of yesteryear. Since the founding and to this day, each gym member has voting rights and anyone can enter the running to join the committee, which plans events and decides how to spend the gym’s money. Every euro of dues paid goes back into the gym: buying and maintaining equipment, upkeep of the building, covering members’ travel to events. And all the day-to-day work keeping the gym running contributed by volunteers from among the membership.

We ascend to the second level: the bodybuilding floor. More people here, more noise, more faffing around. Some of this equipment, Stephen tells me, has been here since he helped load it up in a gravel lorry to move it from the Hercules Club’s old location. That was 1985; he’s been a member since the ‘70s, and reminisces about his first time at the old location.

“I walked into this room, a shed at the back of an old tenement building on Ormond Quay, dingy place,” he says. “There the lads were, stripped to the waist, looking like Greek gods. I was 15 years old and I looked at them like”—here his mouth goes agape and his eyes pop wide—”This is the place I wanna be. Then one of the lads, a weightlifter, comes over to me and says, ‘Well, will ya do it, lad?’ I’m still here.”

His coach and mentor for years was Tommy Hayden, an institution in Irish weightlifting. Hayden was the first, and for quite a while the only weightlifter to represent Ireland in the Olympics, competing at Rome in 1960 in the lightweight category. He joined the Hercules in 1946 and was coaching members until he died in 2018 at the age of 92. Stephen gets nostalgic talking about the auld fellas. They used to come in from work, duded up in their suits and ties, he says. Hit the changing rooms, hit the bench, and push iron.

The Hercules Club in 2025 is a lot less dank than the old days. Government grants and member fees buy brand-new gear when needed. You’re not even allowed to train in your jocks any more, something Stephen credits as making the place more comfortable for female members. It’s still about 10-to-1 on the male-to-female ratio, but the women who are here don’t feel out of place. The two that I speak to mention the community element and the respect for boundaries. Stephen notes another element that attracts the women who have joined.

“They like the grit.”

And there he’s said the magic word, the reason for my obsession with this place.

This is clearly still a working-class place. While Dublin has spent the past 90 years transforming itself from one of the poorest cities in Western Europe to one of the richest, the Hercules Club has an ethic that feels more rooted in the last century than the current.

Stephen makes the point that while the club maintains its proletarian sensibilities, members comes from all rungs on the social ladder. There’s been binmen, firefighters and barristers, as well as at least one sitting judge. “We don’t care if you’re one sort of person or another,” he says. “If you’re a halfway decent person, you can stay.”

That mindset, that openness to constant change, is what makes Dublin Dublin—though of course they haven’t all been decent fellows. It was founded by Vikings, conquered by Normans, and when the Industrial Revolution kicked off, drew people from all over the island like a magnet. Thanks to this influx, it was one of a few pockets in Ireland where the native Irish language survived. When freedom of movement was introduced in the European Union, thousands of people from Eastern Europe arrived seeking economic opportunity. Post-Covid, new arrivals have largely come from South Asia and South America. On my visit, I meet members from each of these communities—except Vikings.

The second floor is also home to the combat room, a boxing gym in miniature. There’s a timer for bouts, a few heavy bags, a padded floor, the standard stuff. A handful of contenders have come through the gym, mostly boxers and MMA fighters, but there’s no one hitting the bags while I’m there. Dublin’s always had a combat sports culture, especially here, north of the Liffey. Crossing the river feels like walking into a more pugnacious place, where people wear less designer and sport more cauliflower ears.

Though the gym was founded as the Hercules Amateur Wrestling and Weightlifting Club, it never truly specialised in combat. There was always a looseness to the mission. Its founder, a British wrestler named George Dale, founded it to be a genuine club, a place where people could congregate around their shared interests, and pool resources to create something greater than they could achieve on their own. Stephen describes the founder as a “man of mystery,” a figure who’s eluded researchers in the years since. It’s said that he moved back to England a few years after founding the club, and that’s the last anyone seems to have heard of him.

The top floor is the cardio room. There’s no one here. No surprise, considering how many members are powerlifters. (This is a joke. Please don’t squat me.) There’s a decent view of neighboring rooftops. I’ve always admired Dublin’s brickwork—the best masons in the country did their apprenticeships here.

Also at the top level is the office where the committee hold their meetings. They aren’t a very formal affair. The committee discusses the annual club competition, breaks up the budget to be distributed to sub-committees for spending, and makes plans for special events. Currently, the bulk of the work is planning for the 90th anniversary bash, which they’re aiming to hold later in the summer.

There’s a trophy display on a shelf and stacks of many, many more pictures. Stephen shows them to me as he might family photographs, because, to him, that’s what they are. There’s a plaque dedicated to the first club member to clean and jerk 300 pounds, pictures of exhibitions they used to hold on St. Stephen’s Green, and then there are photos of Tommy Hayden. He pauses when he shows these to me, and makes sure I get snaps of them without glare.

We make our way back downstairs to finish our conversation. I’m sat on that ancient lat pull-down, which looks to me more like a piece of fishing equipment than an exercise machine. But this contraption has built the backs of Olympians.

Something that’s struck me so far about the gym is how open it feels, and is. This place is Dublin history! Shouldn’t it feel a little more … exclusive? But joining the gym is as simple as filing out a form; no recommendations required. Staying in the gym means paying dues on time (€295 annually) and observing the club’s constitution—a set of rules that mostly boil down to respect for fellow members and respect for the equipment. I ask Stephen why, being so proud of this place (he’s used the words “family” and “special” more times than I can count), he’s not more protective of who gets to join the family.

“We want to be here another hundred years,” he says.

That “we” stands out. He’s not talking about the committee or the current members, none of whom are likely to be pumping much iron a century from now. The club is “we.”

“It’s your legacy,” I venture.

He points at me like I got the right answer in a pub quiz. Now I’ve said a magic word.

I don’t think Stephen’s legacy will be lifting advice, much of which he learned from the auld fellas, that he passes on to the next generation. They’ll use some of it, sure, but every sport evolves. The collective wisdom of the past is strafed by the razor of competition, and that which stands out as useless is chopped off without ceremony. But the Hercules Club old guard is teaching something more valuable, more lasting, than lifting queues or how to find your optimal stance for a snatch: how to build and maintain a community. It’s something you could spend a lifetime studying, even experiencing, but to teach it requires demonstration. It’s built off the back of decades of voluntary labor, conscious inclusion, putting principles ahead of profit. It requires trust, even faith, in your fellows.

That’s why and how the Hercules Club survives: its members. They want a place like this to exist. They’re willing to do the work to make sure it does.