If you’re curious about what hockey photographers do during the offseason, there’s no one better to ask than Bruce Bennett. He is the world’s most prolific hockey photographer and the head of Getty Images’ hockey imagery division. In his 50-plus-year career, he’s shot more than 5,300 NHL games, six Winter Olympics (with a seventh upcoming in Milan), and more than 40 Stanley Cup Finals.

The first thing Bennett does to recover from the grind-it-out pace he maintains during the season, from training camps to the draft, is decompress. “No texts, no emails, no phone calls. I just want to be in my own head for a bit,” Bennett says.

But he can sit and wait for his backyard pool to freeze over for only so long before his trigger finger begins to twitch. That’s when he turns his focus to photographing the birds near his home on Long Island, a bountiful habitat for avian and aquatic wildlife that stretches from the East River to the Long Island Sound to the Atlantic Ocean.

“It gets me some fresh air and some warmth,” he says, “which I don’t get during the hockey season.”

Some mornings, Bennett rises with the sun and heads to Lido Beach, where there’s a 22-acre nature preserve on one side of the main road and a beach on the other. “You can get American oystercatchers and terns and black skimmers,” he says. “You also get egrets on the north side, mostly by the marshland, and they’re diving for fish. There’s enough varieties to keep me busy.”

Late afternoons, he might drive to Centerport or Massapequa, two places that offer views of soaring bald eagles.

He posts his bird photos on the Getty Images wire, just like he posts his hockey pictures. “When a hockey photo of mine gets used now, it’s no big deal,” he says. “But when a photo of mine of a bird swallowing a fish gets used, I’m like, ‘Ohhh, this is awesome!'”

Bennett was born in Brooklyn. His family made the well-trodden exodus to Long Island—Levittown, that fountainhead of suburbia—when he was three years old. He and his wife now live in the hamlet of Old Bethpage, located a stiff seven-iron from Levittown, so he’s practically a native and a lifer.

Though never a particularly fluid ice skater, Bennett played his share of street and roller hockey after school, and he became enchanted with the nightly passion play of the NHL. He grew up rooting for the Rangers, like all hockey fans on The Island did back then, watching Eddie Giacomin protect the nets and the GAG (goal-a-game) line of Hadfield-Ratelle-Gilbert torment opposing defenders. Marv Albert provided the soundtrack: “Kick save and a beauty!”

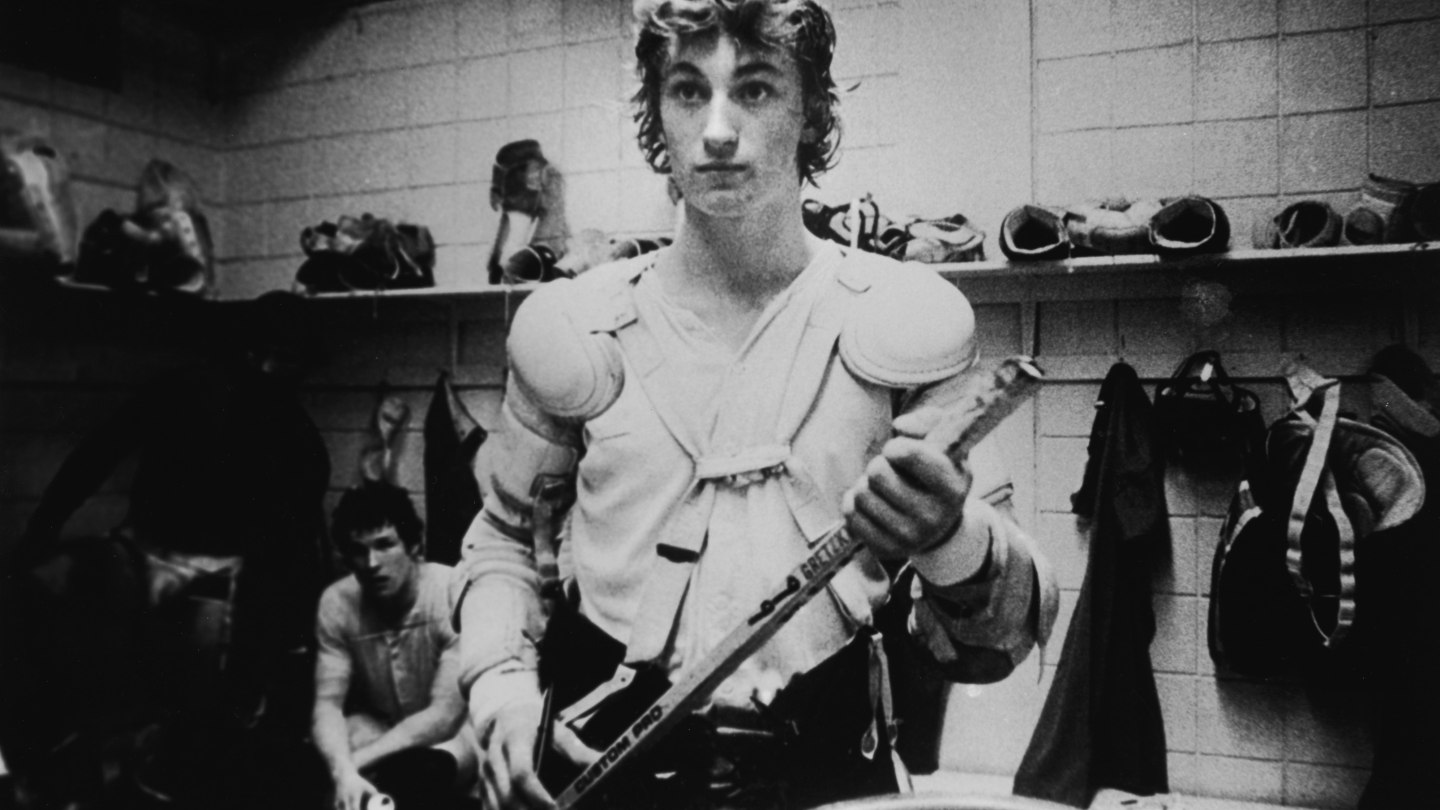

Bennett was attending W. T. Clarke High School when the Islanders joined the NHL and debuted as Long Island’s second major professional sports team. By their second season at the spanking new Nassau Coliseum, in Uniondale, he was “sneaking into the photo box” at the arena, and shooting with his 35-millimeter Yashica camera and 135-millimeter lens from the blue seats at Madison Square Garden. He budgeted one roll of film per period.

Meanwhile, he enrolled at nearby C. W. Post, part of the Long Island University system, to pursue a degree in accounting. He was in his third year when he told his father that he was “thinking about making a change. I’d like to become a photographer.” Bennett chuckles. “Huge mistake.

“I got the finger in the face because he was paying for my college education, a whopping 1,024 bucks a semester. He was like, ‘Oh you will graduate with your accounting degree. If you want to try something else for a while, you can try something else for a while, but I didn’t spend all this money for you to go taking pictures.'”

Armed with his degree and his parents’ support, Bennett’s leap of faith paid dividends, in part because his timing was perfect. After a quarter-century of the Original Six franchises, the NHL was furiously expanding across North America. The league had doubled in size in 1967, adding teams in Philly, L.A., Oakland, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and Minnesota. Buffalo and Vancouver arrived in 1970, with Calgary and the Islanders coming two years later. The success of Swedish defenseman Börje Salming, signed by the Maple Leafs in 1973, cracked open the door to Europe’s vast talent base. Before the decade was out, the NHL would absorb the four surviving teams of the rival World Hockey Association, bringing with them the first true mainstream hockey star, Wayne Gretzky.

Then came the hit 1977 Paul Newman film Slap Shot, and, more importantly, the Miracle on Ice: At the 1980 Lake Placid Olympics, Team USA head coach Herb Brooks’s scrappy, undersized band of collegians rallied to upset the Soviets and then went on to win the gold medal, inspiring a wave of nationalistic fervor and attracting a generation of American-born players to the sport.

All the while, Bennett was learning how to calculate the optimal film speed and aperture to use inside dimly lit arenas, and spending hours in the darkroom. Or, as he quipped, “Getting high on the chemicals—or maybe getting some poisoning from the chemicals. Burning a hole in my parents’ washing machine by having all my chemicals on top of it.”

He mailed prints to Ken McKenzie, the longtime publisher of the Montreal-based Hockey News, then known as the “Bible of Hockey.” Bennett asked McKenzie “if he wanted to buy any of my crappy photos,” and recalls that McKenzie “offered three bucks a pop” and a coveted media credential.

And just like that, as the Al Arbour–helmed Islanders surpassed the Rangers and skated to a Stanley Cup four-peat, and as the players swapped their crew cuts for sideburns and mustaches, Bennett found himself ideally situated to service the growing demand for hockey pictures—traffic permitting.

“The Islanders—that was a 20-minute drive from home,” he says, speaking in 1010 WINS, tri-state commuter tongue. “The Rangers: less than an hour train ride. Then the Devils came to New Jersey—that would be an hour-15, an hour-20. Hartford: I did that trip many times—2:05 was the goal. Philadelphia varied: It was like two hours–45 going down, and a little over two hours coming home under the cover of darkness.”

After games at the Garden, Bennett would open his leatherette camera bag, “and the smell of cigarette smoke would hit me in the face. We also used to have an issue with the stray cats who lived there. Every once in a while, one of the photographers would go, ‘Incoming cat,’ and you’d have to worry about the cat peeing on your camera bag.”

He leaned on veteran photographers for guidance, particularly the husband-wife duo of Joe DiMaggio (insert the requisite “not that one” line here) and JoAnne Kalish. “Joe’s a character—and I mean a real character—and a terrific photographer,” Bennett says. “He and JoAnne, also a great photographer, showed me the ropes soup to nuts, taught me a lot about the business and how to succeed, how to charge clients. All the life lessons that the two of them taught me have stayed with me my whole life.”

Another mentor of sorts was Montreal-based Denis Brodeur, a retired goalkeeper who transitioned to photography not long after backstopping Canada to a bronze medal at the 1956 Olympics. “Denis and I would get together at the Montreal Forum, and he occasionally would come down to see his son play, and we would hang out and talk about business and photography,” Bennett says. “He was an extraordinarily talented photographer who could anticipate the action because he’d played the game. Like now, I’ll shoot 20 frames a second. Back then, with the strobe lighting in the rafters, Denis would shoot one frame, and then he’d have to wait 15 seconds until the strobes were ready to re-cycle and he could shoot again. His images are stunning because of that sense of timing.” (You may have heard of Denis’s son, Hall of Fame goalie Martin Brodeur.)

Bennett threw himself into the craft, scrutinizing the work of creative shooters like Melchior DiGiacomo (who segued to tennis photography) as well as the older masters—the brothers Turofsky (Nat and Lou) in Toronto, and David Bier in Montreal. He studied hockey’s indelible images: Nat Turofsky’s shot of Toronto’s Bill Barilko’s overtime goal that clinched the 1951 Stanley Cup; Ray Lussier of the Boston Record American newspaper catching Bobby Orr fully airborne after he scored the 1970 Stanley Cup–winning goal; Brodeur’s timeless picture of Paul Henderson celebrating his Summit Series dagger with Yvan Cournoyer.

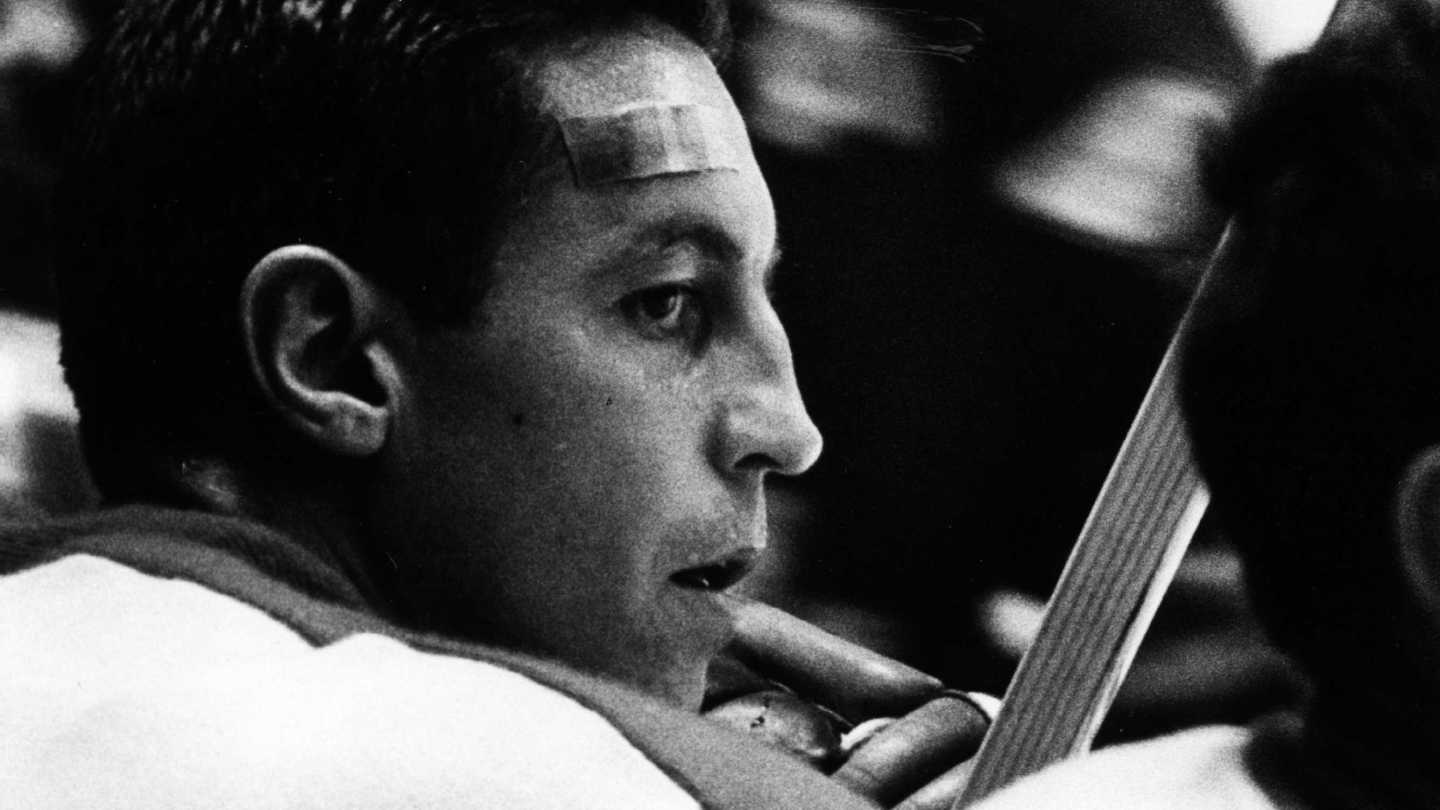

As he transitioned from shooting primarily in black-and-white to color, Bennett paced rink-side to memorize players’ tendencies: who likes to deke and who doesn’t, who prefers to shoot from the left face-off circle, which goalies tend to flop. He learned the hazards involved in covering a violent action sport: Wayward pucks struck him in the head, resulting in a dozen stitches, and in the ribs; he’s had dozens of lenses shattered.

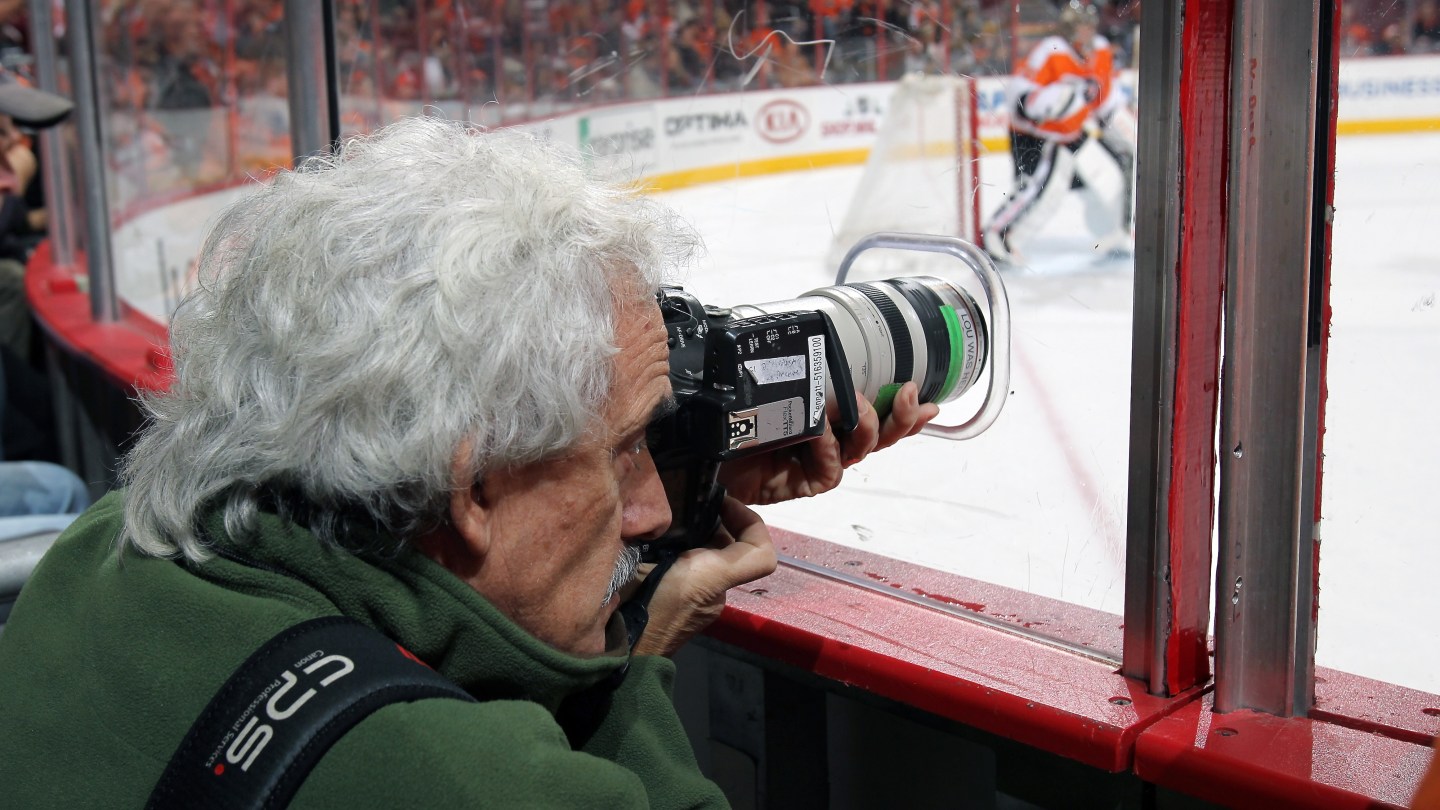

The accrued wisdom helped him overcome the nightly challenge of shooting perhaps the most difficult of the major sports to capture on film: the erratic movements of twitchy-fast athletes balanced on blades and confined to a patch of ice; uneven lighting conditions and the inconsistent glare of a sheeny white surface; the fact that photographers are generally constricted to shooting locations at the corners of the 200-foot-by-85-foot rink and must aim their lenses through a 4.5-inch-by-5.5-inch portal cut into the Plexiglass. The now-mandatory edict requiring players to don helmets and visors, while hugely beneficial for their safety, obscures their visages (and sadly eliminates those dashing images of Guy Lafleur, Ron Duguay, Bobby Nystrom and their gloriously flowing manes).

And that puck: so damn small, so difficult to track at over 90 mph, and bouncing so randomly and crookedly along the ice.

“You know, you adapt,” says Bennett, whose thick mustache wouldn’t look out of place inside a Flin Flon saloon. “You get pushed around from one position to another. Or, you have a remote camera somewhere in the arena, and then they say you can’t put it there, so you gotta go find another location. Or, you’re sitting on a milk crate and it’s not the right height, so you have to adjust and figure out how to get to the right height to see through the holes.”

Of course, for all the glory that he receives for getting “the shot” and scoring a magazine cover, there is invariably regret and disappointment. Four days before the opening ceremony of the 1980 Olympics, Bennett journeyed to Madison Square Garden to shoot a pre-tourney exhibition matchup pitting the U.S. squad against the powerhouse Soviet squad. The ensuing 10-3 rout wasn’t even as close as the score indicated, and inspired scant hope for the Americans in Lake Placid.

“I wish I had shot a ton more [at that MSG game] because it was guys in U.S. and USSR uniforms,” he says. “All the players you’re familiar with, whether it’s Ken Morrow or Dave Silk or [Mike] Eruzione or [Jim] Craig. The whole gang. Those have sold really well over the years.”

He sighed. Intent on his NHL career, he hadn’t bothered to apply for press credentials to the Olympics, even though the upstate New York venue was just a day’s drive away. On his office wall hangs a full-color image of what he missed: Heinz Kluetmeier’s unforgettable photo of the American team’s jubilant celebration on the ice, which became one of Sports Illustrated‘s most iconic covers.

“Nobody predicted something like that,” Bennett says. “While that was happening, I was sitting in my bedroom in Levittown, screaming like any other kid who was a hockey fan.”

He shrugged off the disappointment and moved on. He upgraded his camera equipment from Yashica to Nikon and later switched to Canon; he married his wife and had a son and a daughter. Meanwhile, the old-school style of photography practiced by the likes of his pal Denis Brodeur was being upended. Digital was replacing film, with all the technological advances and accoutrement, like high-speed cameras and faster lenses, integral motor drives and auto-focus, the ability to know immediately if you got (or missed) the shot, the capability to instantaneously transmit images around the globe.

Today, Bennett might carry six or more cameras per game, counting the remotes he places inside the pipes or high in the rafters above the goalies. “It’s a very different ballgame now with digital,” he says. “But you still have to know the players and how to anticipate the action. Even with auto-focus, at times you’re gonna pick up the wrong player or a linesman will cut in front of you.”

What made Bennett so successful, and separated him from many other professional photographers, was heeding his father’s advice. The classes he took while earning his degree at C. W. Post—in accounting, marketing, finance, auditing, and law—prepared him for the cutthroat side of the business, including copyright and licensing, networking with corporate clients, and negotiating with teams and leagues.

While shooting multiple games per week, he established Bruce Bennett Studios (BBS) and signed on as team photographer for the Islanders, Rangers, Flyers, and Devils. He moved beyond North America to land lucrative global editorial and commercial projects, and jumped on the Olympic bandwagon, beginning with the 1994 Lillehammer Games. He rode another boon when hockey trading cards took off in the 1990s. “You didn’t have just Parkhurst and Topps anymore,” he says, “but Fleer and Donruss and Upper Deck and Pro Set and Score. I can’t even remember all the card companies that came and went.”

Bennett hired a staff of 15 editors and photographers to handle the workload. Through a bankruptcy, he acquired an archive of hockey images dating back to the early 20th century that included pioneering players Eddie Shore and Lynn Patrick, as well as a cache of some 3,000 pictures from Russia. He purchased the collections of notable hockey shooters Chuck Solomon and Rich Pilling, as well as Robert Shaver’s photos chronicling the early years of the Buffalo Sabres and the French Connection line of Rick Martin–Gilbert Perreault–René Robert.

“A lot of photographers were equal to me or better than I was, as shooters,” he says. “I was able to make the deals to sell my photos and make a buck. That’s part of the skills that you’re not taught in the photo schools. You find that a lot of creative people don’t have that gene.”

In 2004, Bennett sold BBS to Getty Images for an undisclosed sum. The company’s catalog of approximately 2 million hockey images was shipped to a climate-controlled facility in Los Angeles for storage, preservation, and digitization. The deal included Bennett staying on to head Getty’s hockey photography branch while also maintaining a steady shooting schedule during the season. These days, he raves about the newly opened UBS Arena, near Belmont Park, where the Islanders have played since 2021, calling it a significant upgrade from their former homes, Brooklyn’s Barclays Center and the Nassau Coliseum.

“It may have been a dump,” Bennett, a Long Island loyalist to the bitter end, says of the Coliseum, “but it was our dump.”

The upcoming season offers an intriguing wrinkle with the 2026 Milan-Cortina Olympics, with NHL players participating on their respective national teams for the first time since the 2014 Games. Using photos and schematics of the two ice hockey venues in Milan, Bennett has already begun plotting shooting locations and remote camera placement with Getty Images’ tech crew.

“It’s a challenge,” says Bennett, who’s shot 259 Olympic contests, with a personal record of 41 games in Beijing in 2022. “Photographers at that level—the ones who are sent to the Olympics by their outlets—they don’t fail. So, you have to be in the right headspace to do your job, you have to be physically ready to do it, and I am. We’ll have a plan for myself and the other Getty Images photographers—where they’re going to be, where the remote cameras are going to be set up—and rely on our experience to make sure that no important historic moment is missed.”

Bennett admits that he struggled at times during the 2018 Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea. “I took on too much,” he says. “I wasn’t smart about it, and I learned from that experience. Physically I got better after that, and I’m smarter about how I do things.

“Although it still seems like, when the Stanley Cup Final comes around, I’m the guy carrying the most shit, so maybe I didn’t learn all that much.”

Bennett jokes that the ideal way for him to conclude his career “would be to get hit by a Zamboni at center ice. You know: red line, blue line, Bruce line.” After cresting 70 last spring, and with grandchildren in the mix, he recognizes that he’ll probably begin scaling back his schedule sooner than later. “It’s hard to think ahead,” he says. “I’m not a big planner that way. When it’s time, it’s time. You don’t want to leave too early and sit and stare at the walls. Right now I could do a game every other night during the season and not even blink twice.”

He envisions spending his retirement still steeped in photography, with time enough for backburner projects, including publishing follow-up volumes to his instant classic book from a decade ago, Hockey’s Greatest Photos: The Bruce Bennett Collection (Juniper Publishing). “I’m thinking of maybe a goaltenders book, a forwards book, a defensive book, USA hockey players, lot of options,” he says.

Another possible “retirement thing” is a book of his avian photographs. During the first year of COVID-19, when Bennett started experimenting with shooting birds on Long Island, he tried adapting the skillset and the camera settings he employed for shooting hockey, but found that these didn’t quite work.

“The biggest difference from hockey to bird photography was the focusing point,” he says. “Typically in hockey we chose ‘one dot’ for focus. It’s the fastest way to get a lens to lock in. That was stuck in my brain when I started with birds. Try putting that ‘one dot’ on a bird like a falcon, at 240 miles per hour, and your rate of success is pretty limited.”

Bennett “rethought the focus pattern and utilized more of the in-camera capabilities in the Canon line, including special ‘animal’ focusing algorithms,” he says. He watched YouTube tutorials and studied what other bird photographers were doing. He downloaded apps to help him recognize the countless species he was encountering; he prefers Merlin and eBird, tools produced by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology that enable users to distinguish birds via photographs and sound and to pinpoint locations where birds have been spotted. He admits to wishing that the birds wore “helmets with numbers on them so I could identify them. There are times you go, ‘Great shot, who is that?'”

The results have proved gratifying. “It’s like, oh my God, I’ve found something so gorgeous to photograph,” he says. “It provides me with a challenge equal to or greater than photographing hockey players.”

When Bennett goes “hunting” for bird photos on Long Island, he gravitates primarily to Lido Beach, Oceanside, Centerport and Massapequa. “I missed the chance for snowy owls at Jones Beach as I couldn’t put the time in, and there is a place near Calverton Cemetery that’s been on my list for a couple of years,” he says. “But it’s always an issue when people talk about what they saw somewhere … yesterday. Today and tomorrow are new days and usually the inhabitants vary greatly day-to-day. At least hockey players always come back the next game.”

He’s drawn toward shooting the larger varieties—or, as he puts it, “I am a big bird guy. Sparrows and other little ones don’t interest me. The blue jays and cardinals that populate my backyard are beautiful, but give me an egret, an eagle, a hawk, or a blue heron any day.”

Perhaps his single favorite is the roseate spoonbill. “There was one, just one, on Long Island last year, and people lost their minds,” he says. “They are in the flamingo family with a gorgeous shade of pink and are kind of goofy-looking.”

Once, on a trip to a preserve in Florida, Bennett espied a lone roseate spoonbill up on a pole. He leaned into another key lesson gleaned from a half-century of shooting hockey—patience—and “just stood there, ready for it, focused and focusing, and saying, ‘I’m just gonna have to wait it out.'”

When the bird took off, he captured it in full flight. “Sometimes the bird wins and sometimes you win,” he says.