Some might say Mike Lucido peaked early. But, by god, what a peak. No high school player in the D.C. area got more attention in the 1970s than Lucido, a running back for the Annandale Atoms from 1970 to 1973. Lucido’s heyday coincided with halcyon times for high school football in the area, filled with intense rivalries for Beltway supremacy. But with Lucido, Annandale (Va.) was the cream of the crop.

“Even if you didn’t really know the guy, if you were around here then, you felt like you did,” recalled Dale Eaton, who’s been a part of the Northern Virginia high school football scene as a player, coach, and administrator since the late 1960s. “There was so much written about him.”

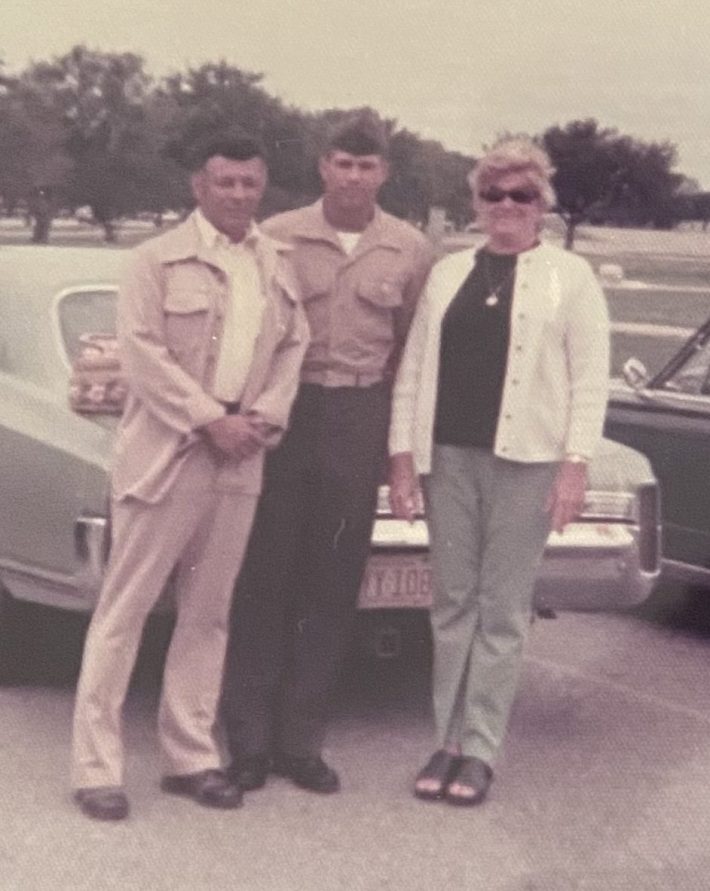

The Lucido legend spawned in the fall of 1970, his freshman year. The story went that his father, Army Col. Jack Lucido, who’d been a football star himself back in high school in Massachusetts, had moved the family from Germany to the suburban community after being transferred to D.C. just as the son entered junior high. Mike told his new friends that Dad had specifically chosen Annandale so he could someday play football at the local high school. These were the peak years of U.S. military involvement in Vietnam, and not long after the transfer, Col. Lucido was ordered by superiors to schedule a one-year tour of the war zone. The boy didn’t want his father to miss him playing any meaningful games, but everyone knew ninth graders typically stood little chance of making the varsity team under iconic Atoms football coach Bob Hardage, who served as the team’s assistant or head coach from 1958 to 1989, winning four state championships and one national title along the way. So Mike asked his dad to take his tour as soon as possible.

“He was going to go last year or this,” Mike Lucido told the Washington Post in 1971, “and I figured since I’d probably be playing freshman football last fall, I’d rather have dad come back and see me play as a sophomore on the varsity.”

Mike Lucido not only made the team; he was a star right out of the gate. Before the first game of his freshman year, the Atoms’ starting running back hurt his leg, and from then on the gig was all Lucido’s. At 14 years old and measuring in at 5-foot-11, 180 pounds, Lucido broke the school record for rushing attempts in a season, and earned All-District honors. Col. Lucido returned from Vietnam in time for the opening game of his son’s sophomore year in the fall of 1971, and, oh, what a welcome home party his son threw for him. The first time Col. Lucido got to see his boy play high school ball, he gained 237 yards on 25 carries and scored both Annandale touchdowns as the Atoms beat defending regional champion Marshall High, 15-7.

Lucido died this spring of cancer, at age 69. Annandale held a memorial service for him on Sept. 26, hours before kickoff of the homecoming football game, with dozens of former players from the school’s gridiron heyday coming to say goodbye to the greatest and most celebrated football player who ever played for the school. Those who showed up also wanted to remember a bygone era from a half century ago, when Annandale had one of the premier football programs in the country, and the game really mattered around here. Or, as those days were dubbed in his senior yearbook, the “Lucido Era.”

At the memorial, several speakers remembered how everyone thought Lucido was older than he really was. He wore impossibly thick hair with dark and bushy mutton-chop sideburns when he showed up at campus. Phil Harmon, who played defense for the Atoms during Lucido’s run, recalled walking around Annandale with his teammate in the summer of 1971, when a local politician came over and starting giving his campaign spiel to Lucido. When Lucido politely told the candidate he wasn’t going to vote for him, the politico’s feelings got hurt. “He says to Mike, ‘You can’t vote for me? Why?'” Harmon said. “Mike says, ‘I’m only 15.'”

Mike Gullette, who would later serve as captain of Annandale’s 1978 championship team, had an older brother who played for W.T. Woodson High School, another fierce Atoms rival during Lucido’s era. “A Woodson guy I knew told me that they had a contest when they played Annandale, to see how many strands of Mike Lucido’s beard they could pluck out in the pile,” Gullette said. “Lucido definitely had a look!”

Teammates figured their coach initially put him on varsity because no freshman could possibly look like that. Then everybody saw Lucido also played like a man among boys. Coach Hardage favored a conservative, run-based offense akin to Woody Hayes’s “three yards and a cloud of dust” scheme. When anchored by Lucido, though, it became six yards and a cloud of dust.

“Acceleration, desire and good balance mark Lucido,” wrote Thomas Boswell in a 1973 profile, one of many Lucido pieces he penned early on his way to becoming a Post sportswriting icon (and recent Baseball Hall of Fame honoree). “He is seldom tackled cleanly, yet he also seldom makes a tackler miss completely. He may survive three glancing collisions in one run. The man who finally gets him is often rewarded with a helmet in the stomach.”

Despite Lucido’s glorious start, the Atoms’ 1971 season ended with a lopsided loss in the regional championship to T.C. Williams, the very squad later immortalized in the film Remember the Titans. The Atoms got revenge in the opening game of the 1972 season, defeating the Titans, 24-15, at Annandale before a reported crowd of 10,000. The Atoms don’t draw that many fans over entire seasons nowadays, let alone a single regular-season game. Lucido ran for a school-record 1,636 yards that year, while carrying Annandale all the way to the 1972 state championship.

Lucido kept putting up big numbers—and getting lots of ink.

He finished his high school career with 5,196 rushing yards, a Virginia schoolboy record that stood for decades. His 54 touchdowns was the second-highest total in state history at the time. Both are still school records. He made the once-prestigious Washington Post All-Met teams three years in a row, and was named D.C.’s offensive player of the year his junior season. He was an All-American as a senior.

In a profile of Lucido for the Post, Boswell asked Jerry Fauls, longtime head coach of rival Stuart High School, for his thoughts on the teen prodigy. Even when speaking about a minor, Fauls couldn’t hold back. “I hate to look at him,” he said.

Perhaps the surest sign of his impact at Annandale was this: The school retired his No. 44 jersey before he even graduated. Lucido remains the only Atoms player so honored. (I’ve been following high school sports for 50 years, and I’ve never heard of any other scholastic athlete having a jersey retired while still enrolled.) His bio in the senior yearbook, which had a multi-page spread on the “Lucido Era,” was straightforward but awesome: “Varsity Football 4 years. All-District. All-State. All-Metropolitan. All-American.” Alabama’s Bear Bryant, and every football school that mattered, recruited Lucido. He ended up taking an offer from Lou Holtz, who was in his second year at NC State.

And then Lucido vanished.

The Post archives contain 54 stories about Lucido written between 1970 to 1973, the years he played football at Annandale; his name has appeared in the paper of record for the nation’s capital only once in the subsequent 52 years. What little information that’s out there about Lucido’s time at NC State makes it seem disastrous. Holtz did tell Technician, the university’s student newspaper, in February 1974 that he was excited by the potential of Lucido and other tailbacks on the roster.

Lucido was credited with just one carry for two yards for the 1974 season. Then John Konstantinos, the NC State assistant who recruited Lucido to Raleigh, left to become the head coach at Eastern Illinois. And while Lucido shows up in the Wolfpack’s 1975 photo albums, his name doesn’t appear in any box score or season stats wrapup that I could find. He left the team that year.

Indeed there was. Apart from Lucido, Holtz’s overall assessment of his stable of runners did prove to be correct. NC State really did become Running Back U around the time Lucido showed up in Raleigh: Stan Fritts went on to play two seasons for the Cincinnati Bengals; Roland Hooks played seven years for the Buffalo Bills, and Ted Brown was a two-time All-American and first-round draft pick for the Minnesota Vikings.

The only published explanation for Lucido’s departure from NC State I could find came from a 1976 column in the Winston-Salem Journal. The article focused on Pete Conaty, the quarterback for Annandale’s 1972 state title team, who went on to be a placekicker for East Carolina University. But while going over the top players Conaty played with in high school, the newspaper’s Mark Whicker referenced Lucido committing to NC State only to “quit when he got lost in the shuffle.” Danny Meier, a Wolfpack teammate of Lucido’s who went on to a long high school coaching career in Fairfax County, Va., told me he doesn’t know exactly what caused the blue-chipper to walk away from the team. “There was steep competition there,” Meier said.

But I’m still stuck on this: One carry for two yards.

Lucido didn’t try to hook up with another college. He immediately joined the U.S. Marines, according to the Winston-Salem Journal’s 1976 report. He got married several times, had three kids, got divorced several times. He remained on active duty until 1991, then worked at car dealerships in North Carolina.

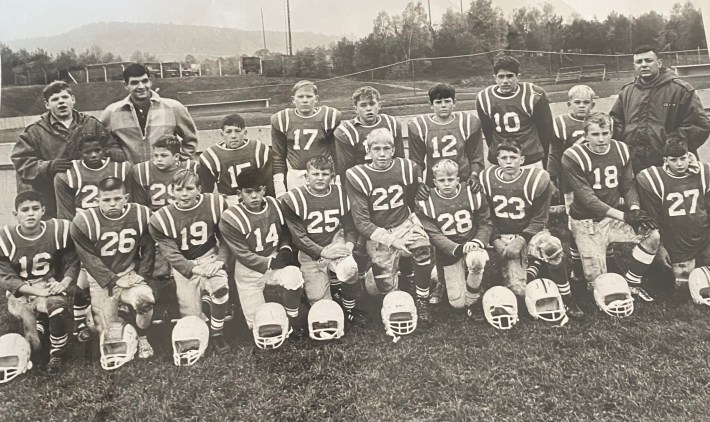

Annandale football continued to thrive in the years after Lucido left. At the memorial, players who followed in his cleat-steps spoke of how much his team’s successes influenced future Atoms and the entire community. Thanks to all the hoopla surrounding the superstar ball carrier and his winning squad, the mood around Annandale in the early 1970s was described as Friday Night Lights meets Happy Days. According to one ex-player, wearing an Atoms letter jacket would bring perks including free slushies at the Highs convenience store, and free meals at the long-departed local eatery Lums.

And every boy in town wanted to get that jacket.

Scot Thomasson, Annandale class of 1979, told me he and all his boyhood pals venerated Lucido and dreamed of one-day wearing the same red-and-white uniform.

“When I was in sixth grade, my father took me to see Mike Lucido play,” said Thomasson, who played nose guard for the Atoms in the late 1970s. “There were these legendary stories about the players that permeated the community, and were used by kids like myself as examples of what you should aspire to. So when you went to play for Annandale, you weren’t just on any team. It was like Sparta, where you have the opportunity to follow in the footsteps of all these guys. You had this feeling that you had to live up to a reputation, created by those that preceded you, and you were expected to carry it on.”

John Bonato, 61, stood up at the memorial to tell Lucido’s former teammates how much they all meant to him growing up. Their inspiration led him to play wide receiver for the Atoms and Hardage in the 1980s, then for the University of Maryland.

“You guys were like NFL players to me,” Bonato said. “When I’d see you at McDonald’s, I’d ask for your autographs.”

The school’s gridiron reputation transcended the neighborhood. The Post ran a real estate article in 1978 that said parents were buying homes in Annandale specifically so their kid could “play on what they consider to be the best football team in the area.” The piece cited Lt. Col. Jim Hatch, a cryptologist for the U.S. Marines and former football player for the University of Florida who’d been transferred from London to D.C. a year earlier. Hatch bought a house in the Annandale zone specifically so his son, Jimmy, could play ball for Hardage.

“Living in England, we were told if you’re moving to Northern Virginia, go to Annandale,” the younger Hatch, now 63, told me recently. Hatch said in his years at the school, he met lots of other military sons whose families also found out about Annandale football while living overseas. The real estate decision ended up working out probably even better than their father dreamed: Hatch ended up playing fullback at Annandale and being a key part of the Atoms’ 1978 squad, which won a state championship and was ranked as the top high school team in the country. He later got a free ride to play at Wake Forest.

In 1979, the Post named the Atoms the team of the decade for the entire D.C. region, atop the more moneyed private schools from the city’s Catholic League and T.C. Williams, another public school that had more than double the enrollment of Annandale in Lucido’s day. Annandale was never known for having the most talented players. Perhaps the most amazing stat about Annandale football, considering all its successes, is this: Just one Annandale player ever made it to the NFL, Ray Crittenden, who played only half a season for Hardage in 1987, his one year at the school.

Hardage, as was said about Bear Bryant and all the greatest coaches, really could take his’n and beat your’n, then turn around and take your’n and beat his’n. I grew up in Falls Church, Va., a block and a half off Annandale Road and one neighborhood over from the school. As a kid, I heard all about Lucido and the Atoms. I was also mystified that the team from a neighboring school about the same size as my Falls Church High was always light years ahead of us. (Thanks to Annandale archivists, here are my Falls Church Jaguars getting destroyed by the eventual national champion Atoms, 37-0, in 1978; I’m the right tackle in the No. 54 white jersey getting beaten on every play.)

I got my answer in 1989, when I covered Hardage’s final game at Annandale, a playoff loss to Dan Meier’s eventual state champion West Potomac High squad. They allowed me in the locker room at halftime. Near the end of the break, the Annandale players got dead silent when Hardage started pacing back and forth and repeating one simple couplet—”Keep your poise. Play the game the way you were taught to play it”—over and over, in steadily increasing volume, from a whisper to a scream. At the time I thought Hardage’s last pep talk was the greatest spoken-word performance I ever witnessed, and that stands. I still get goosebumps remembering that speech, and I pity everybody who wasn’t there to see it, the way I pity anybody who never saw Led Zeppelin live. I haven’t wondered about Annandale’s football successes since.

Hardage is now 90 and living in southeastern Virginia. Health issues prevented him from attending Lucido’s memorial.

Dick Adams, a star offensive lineman for Annandale during the Lucido era and a disciple of Hardage, took over as Atoms head coach in 1990 and was able to maintain the gridiron greatness for a bit, with two state titles in his first five seasons.

But the Atoms have posted just one winning record in the past 17 years (not counting a COVID-shortened half season in 2021), and haven’t won a single playoff game in 31 years. Annandale games lost their big-event vibe eons ago. The school’s administration declined to provide attendance figures for this year’s homecoming game against Park View, held on the night of the Lucido memorial. But it’s safe to say the game drew a fraction of the crowd a Lucido-era homecoming would attract. Halfway through the second quarter of a tight game, the home grandstand wasn’t even half full, and just 34 fans, literally, were sitting in the visiting bleachers. Park View ended up winning, 12-11. The Post did not publish any write-up about the game.

Yet for folks of a certain age, Annandale’s reputation as a football school will always be sturdy. To wit: In 2018, a community news website, Annandale Today, reported then-principal Tim Thomas went out to the parking lot and ran into the school’s most famous alum, Dave Grohl, and a camera crew. The Nirvana drummer and Foo Fighters frontman attended Annandale briefly before dropping out in the mid-1980s to pursue a rock career. He came back to campus to film an autobiographical documentary. After decades away, Grohl wanted to know what anybody former student would want to know about the school.

“Dave Grohl walked up,” Thomas said, “and asked about the school and the football team.”

Bob Grimesey spent the early 1970s as a backup center at Annandale and first-string admirer of Lucido’s. At the memorial, Grimesey was among several former players who talked about how Lucido cut ties to his old school after graduation.

Yet through the decades he was gone, Grimesey made clear, Lucido was never forgotten back home. In January 2024, when Grimesey signed on to help organize the 50-year reunion for Annandale’s class of 1974, he decided getting Lucido to show up was “a matter of public interest.”

“I hate to make it seem like Mike was more important than everybody else,” he said, “but Mike was more important. He was the one guy who tied us all to that time, and it was a magical time for us. We have memories of our parents at all the football games, and grandparents at the games. Mike represented something.”

But Grimesey couldn’t find anybody from the class who even knew how to reach Lucido, who hadn’t shown up to a class gathering since graduation. The kid everybody from high school idolized had fallen completely out of touch with teammates and classmates over the decades. A few alums told Grimesey they’d heard Lucido was dead.

Finally, through Hardage, Grimesey confirmed Lucido was alive and living in coastal North Carolina. Grimesey described being as nervous as a schoolboy asking out a prospective prom date as he prepared to cold-call Lucido. He confessed to being very afraid the one-time biggest man on campus wouldn’t remember him.

“I was only on the field with him for two plays,” Grimesey told the memorial crowd, to many laughs. Both plays ended up being long Lucido runs, Grimesey proudly added.

Alas, when they finally spoke, Lucido told Grimesey he remembered him all the way back to junior high. “That was before he went on to be famous and I went on to carry tackling dummies to practice,” Grimesey said.

Grimesey told Lucido how much he and everybody else from school still thought about him, and he was touched by how much this once-giant figure also appreciated being remembered, even by a backbencher.

But the story Lucido told of his post-Annandale life was a rough listen. Grimesey recalled Lucido saying that he left NC State because he didn’t feel he was getting a fair shot from the coaching staff or professors. In the Marines, he turned down overseas deployments that might have advanced his military career, thinking that staying stateside was needed to save his first marriage, but it broke up anyway. So did all his other relationships. He’d been living in physical pain from a variety of health ailments since the 1990s and was discharged from the Marines on disability after both knees gave out, which Lucido told him was a result of the pounding he’d taken at Annandale.

Then he had a heart attack, and related cardiac problems made keeping the car dealership jobs difficult. He’d recently been diagnosed with terminal bladder cancer. Grimesey went to visit Lucido just after he’d finished a month of radiation and chemotherapy regimens, and he was shocked by how frail Lucido looked.

For Grimesey, hearing the tales made the distance Lucido had put between himself and his oldest friends even sadder to accept.

“His life cannot end this way,” Grimesey said he told himself. “It just cannot.”

With Lucido’s blessing, Grimesey began to reach out to old Annandale football guys who had also gone decades without having any contact with him to catch them up. He then set up a network of Atoms football vets to make road trips to see Lucido, participate in Zoom conferences, or get on the phone with their ailing hero.

The goal of all the communications with Lucido, one Annandale teammate said at the memorial service, was to “take him back to when he was king.”

According to Grimesey, except for an unplanned and brief encounter in the late 1970s, Lucido and ex-Atoms QB Conaty hadn’t spoken since high school. But Conaty got in on the summits.

So did Lou Bonato, a lineman during Lucido’s Atoms career (and John Bonato’s older brother). Bonato said he and Lucido were “inseparable” in high school. Then Bonato went to play ball for the University of Richmond, and Lucido took off for NC State, the Marines, and life.

“And we went 40 years apart,” Bonato said.

Bonato, now living in New Jersey, told me he had no idea why Lucido became estranged from him or the other Annandale guys. He wondered if it was because Lucido felt he couldn’t face the folks back home after flopping in Raleigh, or if life just got in the way. But once Grimesey brought them back together, Bonato said, he was determined to spend whatever time Lucido had left as his best pal again. Bonato drove down to North Carolina for several visits, and he and Lucido set up a standing phone date, every Sunday at 9 a.m.

“It was just like old times between us,” Bonato said. “That’s what real friendship is.”

Lucido still had all the scrapbooks his mom, Sally Lucido, made during his glory days at Annandale, several binders thick with faded newspaper clippings and photos. Lucido gave them all to Grimesey to share. (Grimesey has made much of the scrapbooks’ contents available online.)

During a group visit to Lucido in August 2024, Grimesey accomplished his original mission: Lucido promised he’d come back to Annandale for the 50th reunion last year. And, a month later, he did. A gang of football alums got together at a bar near the school for their own shindig before the main event, and all hailed Lucido for showing up. One member of this band of brothers brought DVDs of several games from the 1972 state championship season that had been digitized from 16mm film. Much like Lucido himself, footage from that glorious year had disappeared years earlier and was thought lost. (Grimesey posted the recovered games online.)

But terminal is terminal.

Lucido was invited back to Annandale for another football soiree in November, but he didn’t show up because of his cancer. In the spring, he went into hospice care in Greenville, N.C.

On May 9, 2025, Grimesey heard Lucido was fading. Grimesey sent out word through Annandale alum channels that anybody who had any message for Lucido better get it to him fast, then went to see him. Lucido’s daughter-in-law and granddaughter were there when he showed up, but Lucido was unresponsive. Grimesey played the videos he’d posted on YouTube from Annandale’s 1972 state championship season, and told the kid that No. 44 was her grandfather, and this was proof that he was “a stud.”

The family members went home in the early evening, leaving Grimesey and Lucido alone. Grimesey sat bedside and put his phone on speaker to play calls and voicemails from old Atoms as they came in. Lucido still wasn’t showing any real recognition. Then Grimesey played a recording of the Annandale fight song:

Fight on for Annandale

Wave the red and white

Grab that ball and watch ’em go

For Annandale tonight

Go, Atoms, and knock ‘em cold

Fight and never die

Victory will be our goal!

Lucido, he said, began stirring. After Grimesey turned off the music, Lucido raised an open palm. He’d been taking it all in. Grimesey clasped Lucido’s hand and stroked his hair until the grip went limp. For several minutes he just stared at Lucido, as the life of a guy he remembered as “a mythical, god-like character,” slipped away.

“I was looking at him lying in bed,” he said, “and mainly thinking that was my friend, Mike.”

Before leaving his pal for the last time, Grimesey read Lucido a text Hardage had sent that night. The old coach, too, wanted Lucido to be king once more.

“Mike, we’ve got the ball on the Woodson nine-yard line and a chance to win. But it’s the last play of the game. You are the one that I want to get the handoff and win it for us,” Hardage wrote. “I’m glad you were on our side.”

Lucido died the next day. The first line of the obituary posted by a North Carolina funeral home: “Mr. Lucido was a legendary running back whose name is synonymous with Annandale High School’s (Va.) storied football legacy of the late 20th century.”