This spring, a new business opened on the main drag of my West Philadelphia neighborhood, provoking both excitement and trepidation.

“I saw it just the other day and feared it,” one friend texted. “Like what the actual fuck is that shit,” said another. “Why?!!!” said a third. “Who is that for?”

Until last summer, the corner storefront at Baltimore Avenue and S. Melville Street was a moderately overpriced hipster vintage store. After it closed, it sat empty for nearly a year. Then, in March, it sprang to life.

A “grand opening” banner went up over the door. A miniature wacky inflatable tube man flailed around outside. Posters with the logos for Walmart, Amazon, Costco, and Best Buy covered the windows, declaring “CRAZY DEALS, AMAZING BINZ.” I had to check it out.

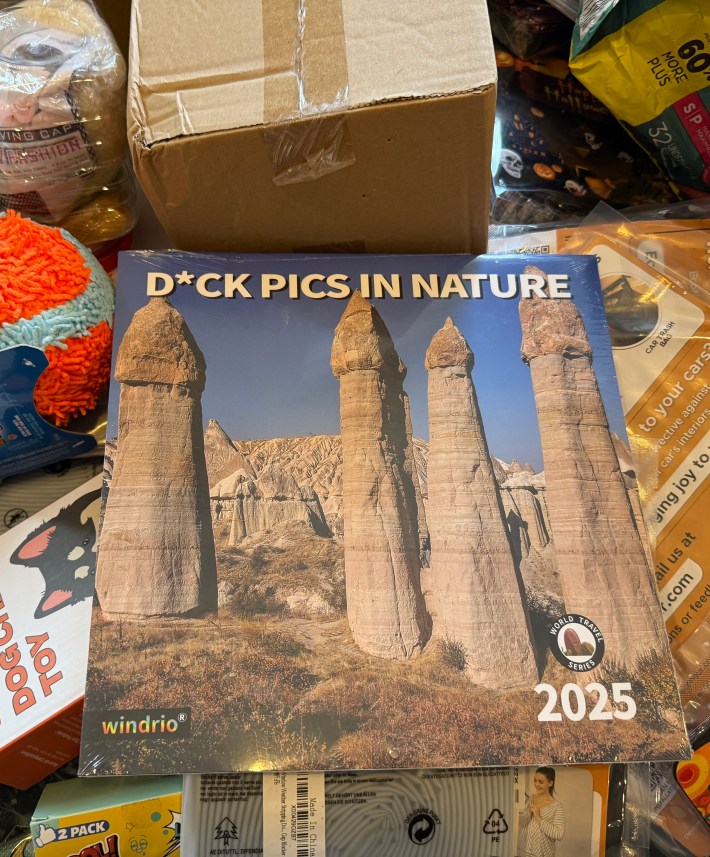

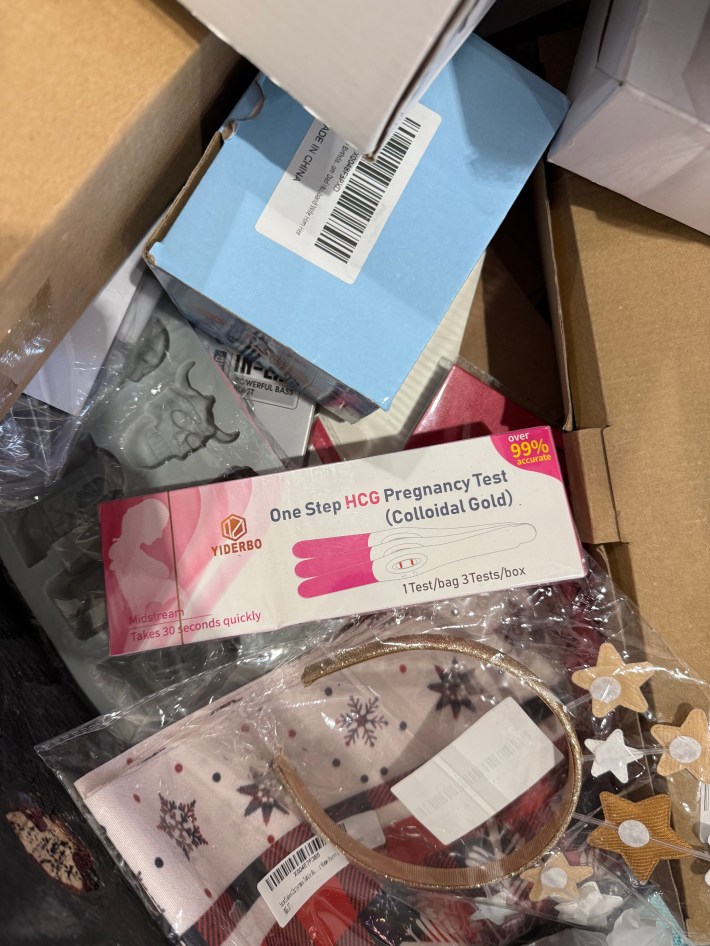

AMAZING BINZ is on the first floor of a rowhome, narrow and long. There’s one central aisle, and on either side, big wooden tray tables—the proverbial binz—overflowing with undifferentiated piles of consumer stuff: unopened Halloween costumes, an ice mold shaped like a penis, a banner of many glittery penises wearing grass skirts, a staggering number of “reusable hot and cold gel compression sleeve[s] for elbow,” a single loose pregnancy test, something called Wokaar for “waxing the nose beard.”

At least half the products are still in boxes, and there are signs on the walls warning customers to NOT OPEN THE BOXES, so you have to scan the barcode with your phone or decipher clipped product descriptions: “module stool,” “gratitude journal,” “Xmas tea light green.” But the great innovation of Amazing Binz is its pricing structure, which is splashed across the facade in Spanish and English and makes good on the promise of CRAZY DEALS. On Fridays, when the bins are freshly stocked, everything costs $10. On Saturdays, $8. Sundays: $6. Mondays: $4. Tuesdays: $2. Wednesdays: $1. Thursday is bin store Sabbath, when the shop is closed and restocked.

The store is like nothing else on the block, which boasts, among other things, a yoga studio, two vape shops, a volunteer-run book store and a Marxist reading room, and no fewer than four Ethiopian joints.

Where did all this stuff come from? Who opened this store, and why? Is it profitable? What does it mean for the uneven gentrification of Baltimore Avenue and West Philadelphia? I decided to spend a week visiting Amazing Binz every day. Here is what I found.

Thursday: Restock Day

On Thursdays, Amazing Binz is closed. One of the owners, Ahmed, has graciously allowed me to observe the restock. Overall, Ahmed has been very gracious about my fixation on his store.

When I arrive at 10:30 a.m., he’s smoking a cigarette and nervously awaiting a delivery truck with 18 pallets of mixed merchandise from Target. Amazing Binz gets its inventory from major corporations’ overstock and returned products, taking advantage of the vast weird world of “reverse logistics.”

“ You’ve got the front end, where you order the product, it comes into the port, it goes to a warehouse, to a store, and then to our front door,” says Cathy Roberson, a researcher at the Reverse Logistics Association, an industry trade group. “What if once it hits our front door, we don’t like it, or it’s broken or something? That’s the reverse part. ”

Returns, repairs, refurbished products, and even recalls fall into the purview of reverse logistics. They are joined there by products that never made it to a consumer because the season ended, or a box was a little dented, or the purchaser never picked up their order, or a retailer was just running out of room in their warehouse.

That pile of excess stuff is growing. About 17 percent of all merchandise gets returned, according to the National Retail Federation. That’s up from just eight percent in 2019. For online purchases, it’s almost 30 percent.

Liquidators are nothing new: T.J. Maxx, Ocean State Job Lot, Nordstrom Rack. But as the scale of the excess grows, the reverse logistics industry is expanding, and methods of disposal are diversifying. Some corporations, like Amazon, do their own reselling through a bulk liquidation page. There are middlemen like B-Stock, an eBay-like site where anyone can shop for truckloads of unwanted stuff. Influencers are buying pallets to unbox on stream, capitalizing on both the goods and the views. It’s a whole universe of brokers, wholesalers, and secondhand retail all trying to claw back a little bit of money from the growing pile. That’s where Amazing Binz comes in.

“The goal for all the reverse logistics stuff,” says Roberson, “is to keep things out of the landfill.”

Today, Ahmed is expecting half a truckload with about 3,500 to 4,500 individual pieces, ranging from kitchen appliances to toys to clothing; he doesn’t know exactly what. The semi-truck pulls up right on time, and Ahmed unloads it with a forklift, cigarette still in mouth. Pallets fill the sidewalk, glistening shrink-wrapped towers of stuff: air fryers, microwaves, a vacuum, a sled, a machine that tosses a football, My Little Pony-branded diapers, and a go-kart.

Inside the store, the bins are still half-full from the last truckload, which came from Amazon. There are many products I’ve only ever seen on the internet: a carrying case and monogrammed straw cover for a Stanley cup, a big plastic grinder for shredding chicken, silicone molds for making the viral Dubai chocolate bar at home.

For this restock, Ahmed was hoping for a different caliber of item. It’s a mixed success: some quality products, but more clothing and returned items than he was hoping for. Electronics are the holy grail; appliances and home goods do well, too. The best items are the ones that retain their value, because Ahmed sees his customers as agents in the reverse logistics economy, too.

“You can buy stuff from here and then you can resell it,” Ahmed tells me. “Through eBay or Amazon. You can sell on Facebook market. You will get your money back in less than one day if you wanna resell it. Which is a good thing for everybody right now, for the public. A lot of people need to work.”

It’s a slog of a day. I leave after a few hours, and come back at 6:00 p.m., nearly eight hours into this operation. Ahmed and two helpers are still unloading and stocking. They won’t be done until after 10:00 p.m.

Friday: $10

I get to Amazing Binz at 9:35 a.m. It opens at 10:00 a.m. Already, two people are standing at the door with their faces pressed to the glass.

Soon, six people are waiting, then a dozen. A woman and her kids show up in a taxi. At least one person has come from the county over. Amazing Binz posts their new hauls on Instagram, so some people have already scouted what they want: a kid’s scooter, a shower caddy. Fridays offer the highest upside: a chance to score something really valuable for just $10. All the real shoppers are lined up this morning, looking for an edge.

People are arriving every minute; the line swells to 25. Most of the people waiting are middle-aged black men and women. Some are resellers, and many seem well-versed in Philadelphia’s liquidation economy. A few bring up Turn 7, a giant liquidation warehouse with a bin model that closed last month. I learn about another bin store in New Jersey, and one in Northeast Philly called Black Friday Outlet, a nationwide bin store chain. Someone tells me there’s another bin store opening up today, just 10 blocks away.

“When I first got into this industry, there were no more than 10 bin stores in the entire country,” says Nebraska-based wholesaler and content creator Colton Carlson, who opened his first store in 2018. “Fast forward a few years, [and] there ended up being 3,000 bin stores.” Today, he thinks there could be as many as 10,000 in the U.S.

Bin stores are distinguished by their pricing model—a set price per item or weight, and falling prices to incentivize quick sales—and by their agnostic approach to inventory. They’ll take nearly anything and everything.

“Once people caught on that you could buy a truckload of inventory, you dump it in your bins and you make a ton of money, then they really just started opening that rapid-fire at that point,” says Carlson.

The explosion of online returns got the bin-store craze started, but the pandemic put it into overdrive. Factory shutdowns and slowdowns at ports meant for weird lags in the supply chain that led to seasonal products arriving past their season, or goods just being abandoned at port. To try and weather the uncertainty, and keep up with exploding online shopping, retailers overstocked on inventory.

“In the beginning of the pandemic, we bought everything in sight,” says Roberson. “Then all of a sudden we, the consumer, decided we’ve had enough. We’ve bought everything. We’ve gotta tighten our belts now.”

Consumer spending dropped, and retailers were left holding the bag in overstuffed warehouses. Some, like Target, “ kind of got caught with their pants down,” says Roberson. They were stuck with so much excess inventory, they sold it for pennies on the dollar. The secondhand market flooded with more cheap stuff than normal, creating opportunities for resellers.

“On opening day, we had about 300 people lined up down the street,” says Carlson, who thinks his was the biggest bin store in the country at the time. “Every weekend from that, it was just the same thing: a line down the street with 200, 300 people ready to find a deal.”

This Friday morning at Amazing Binz, there are now over 30 people waiting to be let inside.

Finally, the doors open and the crowd floods into the narrow shop, honing in on the premier items. Scooters and grills and Target-branded home goods fly out of the bins. People are hauling around air fryers so no one else can take them. It is, frankly, a bit of a mad house. One reseller, who didn’t find anything he wanted, says, “One of these days, someone’s going to get shot.” A woman declares, “I will never do this again.”

Generally, people seem happy with their finds. The guy who wanted the scooters gets the scooters; the woman who wanted the shower caddy gets the shower caddy. It all happens fast. By the end of the day, the first two bins are completely empty.

Saturday: $8

It’s farmer’s market day in West Philadelphia, Baltimore Avenue’s busiest day. The store is much calmer than Friday morning, but still doing a brisk business. Where yesterday there were piles of home goods and appliances, the bins have been restocked with less high-end fare: soccer balls, bike inner tubes, sand art kits, clothing, shoes.

I want to get a sense of how neighbors are feeling. Once, while digging in the bins, I heard a young guy muttering to himself. “This is so weird. What am I looking at?” We made eye contact. “Have you ever seen a store like this?” he asked me. “It doesn’t feel right. I don’t think this will be here long.”

I check West Willy, the easily parodied local Facebook group. A post about Amazing Binz has over 50 comments, ranging from “omg I am EXCITED,” to “Maybe I can find things I need and not weep over the price,” to “No offense to the owners but this store feels like where late stage capitalism goes for one final hurrah.”

I ask the book vendor who sets up outside the Marxist storefront how he feels about Amazing Binz. “It shows the corporation’s incursion into the neighborhood at every level, big to small,” he says. He adds that he likes that it’s a minority-owned business.

I ask a resident who happens to be walking by, a long-timer who moved to the neighborhood in the 1970s when it was, as he says, Philadelphia’s answer to Haight-Ashbury. “It means a potential downturn of the local market that had been popping up with restaurants and boutiques,” he says.

Baltimore Avenue runs from the University of Pennsylvania campus in the east, west through a neighborhood that’s a mixture of million-dollar houses, squats-turned-group-houses, and some of the city’s most persistent poverty. For the six-ish years I’ve lived here, I’ve watched a handful of bougie businesses open and quickly fold, leaving behind empty storefronts. Housing prices just go up and up, but the retail strip suggests an uneven gentrification. Those fluctuating fortunes are mirrored in starkly divergent views of whether Amazing Binz is an “amazing store with amazing stuff and amazing prices” (their first Google review) or “a place that sells crap” (a post on West Willy).

It’s an odd location for a store like this. Liquidators usually look for huge spaces, in industrial areas or big shopping centers at the edge of town. When I ask Ahmed how he came to open Amazing Binz here, he said it was actually not his first choice. He wanted to open a cafe or a sweet shop, but says he couldn’t get the permits or the zoning. The landlord wouldn’t give him a break on rent, which is nearly $4,000 a month.

So after about eight months of sitting on the location, Ahmed decided he needed to open something with low overhead and little startup capital. There’s a few bin stores in Northeast Philly, where he lives, so he’d seen this model before, and thought it would be good for the neighborhood. At the start of this week, he hung a Free Palestine flag behind the counter. He’s from the West Bank and felt comfortable hanging the flag because, he says, “Our neighbors support us.”

Nearly every time I’m here, there are happy customers, usually quite a few. There’s a real mix of the neighborhood. Serious diggers, often in headphones, methodically overturn every pile. A PTA mom sends her husband home for the car after she fills three baskets with school supplies. Some gigglers revel in the slop and the strangely sentimental: the Dick Pics in Nature calendar, the crystal heart paperweight engraved with a 25th wedding anniversary message.

But there are haters. At parties and potlucks across West Philadelphia, my neighbors split into camps: for or against the bin store. Houses divide against themselves. Pros: It’s cheap, it’s fun, and at least the stuff isn’t getting thrown away. Cons: An uncanny feeling of glimpsing the collective consumer psyche, AI slop in consumer form, the horrors of production for production’s sake.

At the farmer’s market, a friend of a friend calls Amazing Binz “dark and sinister,” and compares it to a big sifting funnel. All the consumer drivel of the world goes in at the top, and all the unsaleable, undigested, unwanted stuff just falls out the bottom. “The bin store,” he says, “is like the last step before they just throw it in the ocean.”

Sunday: $6

When I get to Amazing Binz, Omran—Amazing Binz’s social media hype man—is filming a video with a shopper who found the toner she usually buys at Sephora, for $65, here in the bins for $6.

This is one of Omran’s Instagram shticks. He asks customers what they bought and how much they paid, and then replies, “I know daht’s right,” a phrase also tagged on all the posts.

Omran does some of the ordering for Amazing Binz. He says he buys his inventory through direct relationships with people at warehouses, not through auction sites, where the prices are often higher. Ahmed tells me the average truckload costs about $16,000, and will contain thousands of individual pieces. The key is to keep the cost per item at around $2, and to get a mix of higher- and lower-value items so they balance each other out.

Most bin stores do a hybrid model, where they sell higher-quality stuff on the side at prices above $10. Amazing Binz calls it the VIP section. With this week’s Target haul, I assumed that the nicer items would end up there. But no, the owners priced most of it at $10, hoping the allure of a huge discount on a big-ticket item draws people in and gets them to spend more.

This is the bin-store promise: teasing the chance to find Oura rings and AirPods for just $10. Once, while I talked to Ahmed, a neighbor walked by and waved. “She got those Beats headphones here,” he says. “Ten dollars. She was so happy.”

But the price flattening works in both directions, I realize on a $6 Sunday. A friend is shopping for a mermaid-themed bachelorette party, and we find plenty: That previously mentioned garland of penises is still here (two, actually), as well as a sheet of mermaid stickers and a curly straw that spells “BRIDE.”

The problem is that $6 is too expensive for a straw, especially a straw that I know has been here for three weeks, at least. This is one effect of the bin store: There’s plenty of legitimately good stuff, at good prices, but that usually gets snapped up in the first few days. Anything that remains through the whole pricing cycle and back again is revealed to be worth nothing at all.

My friend, digging for penis straws, says maybe it’s good to see. We have to confront this stuff. This is the cost of our collective Amazon addiction.

There are times when the bin store does feel like an art installation, a message, or a warning. Wander through it for a few days and you will start to feel like you are in a room in a haunted house, one where the corporeal forms of the world economy’s least-wanted products are trapped, unable to move on.

With or without Amazing Binz, all of this stuff is just out there, already made. A lot of it is useful but excessive, rendered obsolete by an overheated economy. Shopping here can feel a bit like fighting the last, losing battle of reverse logistics. What can still be made useful enough to be kept out of the landfill, just a little longer?

Monday: $4

It’s a slow day at Amazing Binz, again. This week has been big on gloomy weather, and low on foot traffic. I find a Trump 2024 Punisher logo drink koozie in the pile. These have been popping up in the bins since that first Amazon haul, along with MAGA and Let’s Go Brandon flags. Every time a customer points one out to the owners, they throw it away.

A woman approaches the counter with a pair of leopard-print flats, but the two shoes are connected by a stretchy white loop of elastic that’s gotten tangled up with at least five other pairs’ elastic, creating an unholy rats nest of shoes that she needs help untangling.

On slower days, it’s hard not to wonder how long Amazing Binz will last. Philadelphia may be behind the times. In the rest of the country, the bin-store bubble has started to burst. On YouTube, I find a cadre of wholesale and reselling influencers, including a bin-store niche. I watch their videos touting the model, how easy it is to start one, and how to succeed. Then I watch them change their tunes.

“Unpopular opinion: Bin stores really suck right now,” declared creator Lindey Glenn in November 2023. She linked to Carlson’s most recent video: “Bin store burnout.”

After opening his first store in late 2018, Carlson had a few good years riding high on the novelty of the business model and the glut of unwanted pandemic-era merchandise. But as more bin stores opened, the demand and prices for the same truckloads went up. Colton says that after a while, he was just breaking even on the bins, which at his store, started at a high of only $5.

He found other revenue streams, like selling entire pallets to resellers, and sorting out the niche and expensive products to flip on Poshmark or eBay. But the challenges persisted. The bin store is a finely tuned operation. A broker might promise a great haul with new electronics, and then deliver a bunch of dirty and broken returns. A truckload could arrive late, or not at all, leaving owners in the lurch on what should be their most profitable day. These problems are exacerbated in small stores, like Amazing Binz, where it’s hard to store extra merchandise to weather that uncertainty.

And the stuff itself creates logistical headaches. Boxes get opened, sometimes from theft, sometimes just from jostling around in the bins. Pieces get lost, trash and detritus build up alongside the unsold products, the difference between them increasingly hard to discern. In fact, when it was time to clear his bins, Carlton would dump all of the unsold inventory mixed with trash back onto a pallet and sell the whole thing for $50, with the caveat that the buyer had to go toss the garbage somewhere else.

Carlson saw the writing on the wall. He sold his bin store in 2023. Now he’s focusing on his wholesale business, and opening a side-by-side discount grocery and clothing store, which is where he thinks the secondhand retail trends are headed.

The Reverse Logistics Association has also seen a decline in bin-store fortunes. Roberson says they lost a few bin-store members because of bankruptcy. After the pandemic, “it was getting more difficult to buy up that excess inventory because there really wasn’t excess inventory.”

But economic shocks are good for the secondhand economy. Roberson thinks tariffs could, eventually, lead to another bin-store bump. At the start of 2025, she says, many retailers overstocked on inventory again, filling their warehouses to get ahead of price hikes. That could mean they’ll soon be sitting on overstock, especially if consumers decide they’re not willing to pay higher prices. Supply chain disruptions will produce more excess. Already, goods are stalled at ports around the world.

Roberson predicts a temporary dip in the fortunes of bin-store owners, as secondhand goods get more expensive along with everything else, and then a resurgence. Carlson agrees. “ I think the secondhand market is going to keep growing because that’s the whole reason people are shopping at these stores [to see] if they can save $10. I don’t see consumer spending going down for this industry, or even like thrift stores at all. I think that’s gonna continuously go up. However, the problem’s gonna lie on whoever owns the bin store.”

Tuesday: $2

Ahmed seems extremely tired today. He’s barely taken a day off since they opened, not even for Eid. Everything is pretty picked over. The sand art is all gone, the bedding and curtains. There’s just two soccer balls left. I do my customary scan of the bins, from the back of the store to the front. There’s nothing new, just increasingly empty boxes of gel compression elbow sleeves, loose whippit canisters, and batteries rolling across the bottom.

According to Ahmed, the cost of pallets is going up. On a recent load of electronics, he paid $12 per item. For the time being, Amazing Binz is just breaking even, but it’s not sustainable. Ahmed says he may have to raise prices, and that he’ll even have to reevaluate the whole business in a few months. “This type of business, it’s not for this neighborhood,” he says.

Omran, ever the salesman, is darkly optimistic that they can keep prices low. “Anything to save the community some money,” he says. ”We’re not looking to get rich. Being rich is pointless nowadays. It’s about, how can you survive? How can I feed my kids? How can we pay our bills?”

I’m reminded of a conversation I had with the truck driver, Nick, who dropped off the Target load. He used to drive a taxi, until Uber ruined that. He prefers truck driving, but it was better at the height of the pandemic, when everyone was shopping online.

Around that time, Nick’s wife was a third-party seller on Amazon. She stocked her inventory based on social media trends, a task complicated by the algorithm. The more she looked at videos of, say, people showing off their Stanley cup accessories, the more TikTok fed her those videos, until it was hard to know if people were actually buying them in the real world, or if she was just in an online feedback loop. Plus, Amazon charges high storage fees, so unsold product just sitting in their warehouse cost her money. She quit, and abandoned her merchandise. That’s where a lot of the stuff in the Amazing Binz came from: failing third-party vendors, looking to offload the detritus of brief and bygone trends.

For a second, an image of the 21st century economy seems to come into focus here at the bin store. Nick, his wife, Amazing Binz’s owners, and even me, a freelance journalist, we’re all supposedly free agents, “entrepreneurs,” but in reality, we’re limited to buying whatever gets kicked down the funnel, and flipping it for all it’s worth. It’s like I can see our labor getting discounted by the day. Already, I’ve asked my editor if I can resell a version of this story elsewhere, to recoup a little more of my Amazing Binz investment.

Wednesday: $1

At 6:45 p.m. on Wednesday, a little over an hour until closing time, the shop is packed. Everything is now one dollar.

An elderly woman finds a shoe she likes, a black slide with gold studs all over. But it’s just one shoe. Ahmed is insisting she buy it, and says he’ll keep the other shoe for her when he finds it. “For a dollar you can’t beat it,” he says. He’s in a good mood, joking with this woman and her daughter. She’s apparently been looking for three days.

“Those shoes are really cute,” I tell her.

“Do you work here?” she asks. Maybe I’ve been here too long.

After days of finding empty boxes, I finally find a loose elbow gel sleeve. It is heavy, slinky, comforting. After this, I find many of them, hiding in the bins like eels. Everything swims around the piles, and I revisit them as old friends, including the unopened boxes, known only by their clipped epithets: “Kiss Me I’m Irish wooden sign with lights,” “Lazy Susan for Refrigerator New.” The Jujube Enucleator box is full one day, and empty the next, without me ever seeing what was inside. The Dick Pics in Nature calendar remains, week after week. Who knows how many times these items have been bought and sold before they arrived here, how many more times they might be bought and sold. I imagine it all ending up in the same places eventually: the landfill or the waterways, where it will exist forever, first as choking hazard, then as nurdle.

In the dwindling bins, I find another Trump flag, folded in plastic but unmistakable. Omran says I can have it. I unfurl it, stiff and plasticky, creased into a grid. I don’t want it, but what am I supposed to do? It will end up in the garbage one way or another. I stuff it in my bag.

I ask, “How long have you guys been open?” It’s April 16, and Omran says they opened the doors on March 21.

“I thought it was more than a month,” says Ahmed.

“It’s been a long month,” says Omran.

The Trump flag joins a small museum of items I have purchased since the bin store opened: a cat bed ($10), a felted flower garland ($6), four post-Valentine heart-shaped chocolate boxes ($5 for all), two small spring-form pans ($4 each), a large penis-shaped ice cube mold ($4), four bike inner tubes ($2 each), a box of ant traps that don’t work ($2).

Did I need any of these things? Maybe the ant traps, if they’d worked, maybe the inner tubes. Mostly, I bought them because they were there, the same way I watch an Instagram reel because it pops up next. The irony is that if I were in the market for new pans or bedding, Amazing Binz would at this point be my best local option. It’s also simultaneously the most fun and most unsettling store on Baltimore Avenue, a combination that I find addictive, as many bin enjoyers do.

I take one last lap, back into the farthest corner of the store, where the oldest stuff has accumulated in deep drifts, where the Wokaar lives, now separated from its box. Looking for what? I don’t know. It’s concentrated back here, layers of unwanted product, filtered all the way down the supply chain to this last bin, where it’s piling up like sand. As I stare at the piles, I almost expect them to start breaking down in front of me, each individual item decomposing into a pool of microplastics, what remains of its value finally depleted. I leave the store, and the bins where they are. They’ll be full again tomorrow.